marxism

For the study of Marxism, and all the tendencies that fall beneath it.

Read Lenin.

Resources below are from r/communism101. Post suggestions for better resources and we'll update them.

Study Guides

- Basic Marxism-Leninism Study Plan

- Debunking Anti-Communism Masterpost

- Beginner's Guide to Marxism (marxists.org)

- A Reading Guide (marx2mao.com) (mirror)

- Topical Study Guide (marxistleninist.wordpress.com)

Explanations

- Kapitalism 101 on political economy

- Marxist Philosophy understanding DiaMat

- Reading Marx's Capital with David Harvey

Libraries

- Marxists.org largest Marxist library

- Red Stars Publishers Library specialized on Marxist-Leninist literature. Book titles are links to free PDF copies

- Marx2Mao.com another popular library (mirror)

- BannedThought.net collection of revolutionary publications

- The Collected Works of Marx and Engels torrentable file of all known writings of Marx and Engels

- The Prolewiki library a collection of revolutionary publications

- Comrades Library has a small but growing collection of rare sovietology books

Bookstores

Book PDFs

Document No. 19 The Basic Viewpoint and Policy on the Religious Question during Our Country's Socialist Period TO: All provincial and municipal Party committees; all Party committees of autonomous regions, greater military regions, provincial military regions, field armies, ministries, and commissions within State organs and the general headquarters of the Military Commission of the Central Committee; all Party committees within the armed forces and within all people’s organizations: The Secretariat of the Central Committee has recently studied the religious question and has drawn up a document entitled The Basic Viewpoint and Policy on the Religious Question during Our Country’s Socialist Period. This document sums up in a more systematic way the historical experience of our Party, positive and negative, with regard to the religious question since the founding of the People’s Republic, and clarifies the basic viewpoint and policy the Party has taken. Upon receipt of this document, Party committees of all provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, as well as those of the ministries and commissions of the Central Committee and State organs concerned, should undertake conscientious investigation and discussion of the religious question, and should increase supervision and prompt inspection of the implementation of each item related to this policy. It is the belief of the Central Committee that following from this summation of the religious question, our Party needs to make further progress in summarizing its experience in all other aspects of its work, as well as of its work in each region and department. It should be affirmed that since the smashing of the “gang of four” and especially since the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee, our Party has achieved significant results from the summing up of its own historical experience. The “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic” passed by the Sixth Session of the Eleventh Central Committee is a distillation of this kind of result, marking the completion, in terms of ideological leadership, of the Party’s task of restoring order. Viewed from another aspect, however, that is, taking our Party’s work on all fronts, all regions and departments, the work of summing up our historical experiences is quite insufficient. It is the hope of the Central Committee, therefore, that Party committees at all levels, most importantly at the provincial, municipal, and autonomous region levels, will, together with the first-level Party committees and organizations of the Central Committee and ministries and commissions of State organs, concentrate their main efforts within the coming two or three years on doing well the task at hand. They should undertake conscientious investigation of the work in those regions and departments for which they are responsible, systematically summing up their historical experience, positive and negative, shaping this into a set of viewpoints and methods in which theory and practice are intimately combined and which are suitable to the conditions in their regions and departments. It is the belief of the Central Committee that we need only earnestly grasp this key link and expand painstaking efforts in order to achieve new results and effectively raise the ideological and theoretical level of all Party members, who will then adopt correct and effective methods of work and open up a brand new era as our country goes about the great task of rebuilding socialism in the remaining twenty years of this century. Central Committee Of the Communist Party of China 31 March 1982

I. Religion as a Historical Phenomenon Religion is a historical phenomenon pertaining to a definite period in the development of human society. It has its own cycle of emergence, development, and demise. Religious faith and religious sentiment, along with religious ceremonies and organizations consonant with this faith and sentiment, are all products of the history of society. The earliest emergence of the religious mentality reflected the low level of production and the sense of awe toward natural phenomena of primitive peoples. With the evolution of class society, the most profound social roots of the existence and development of religion lay in the following factors: the helplessness of the people in the face of the blind forces alienating and controlling them in this kind of society; the fear and despair of the workers in the face of the enormous misery generated by the oppressive social system; and in the need of the oppressor classes to use religion as an opiate and as an important and vital means in its control of the masses. In Socialist society, the class root or the existence of religion was virtually lost following the elimination of the oppressive system and its oppressor class. However, because the people's consciousness lags behind social realities, old thinking and habits cannot be thoroughly wiped out in a short period. A long process of struggle is required to achieve great increases in production strength, great abundance in material wealth, and a high level of Socialist democracy, along with high levels of development in education, culture, science, and technology. Since we cannot free ourselves from various hardships brought on by serious natural and man-made disasters within a short period of time; since class struggle continues to exist within certain limits; and given the complex international environment, the long-term influence of religion among a part of the people in a Socialist society cannot be avoided. Religion will eventually disappear from human history. But it will disappear naturally only through the long-term development of Socialism and Communism, when all objective requirements are met. All Party members must have a sober-minded recognition of the protracted nature of the religious question under Socialist conditions. Those who think that with the establishment of the Socialist system and with a certain degree of economic and cultural progress, religion will die out within a short period, are not being realistic. Those who expect to rely on administrative decrees or other coercive measures to wipe out religious thinking and practices with one blow are even further from the basic viewpoint Marxism takes toward the religious question. They are entirely wrong and will do no small harm.

II. The Religions of China There are many religions in China. Buddhism has a history of nearly 2,000 years in China, Daoism one of over 1,700 years, and Islam over 1,300 years, while Roman Catholicism and Protestantism achieved most of their development following the Opium Wars. As for the numbers of religious adherents, at Liberation there were about 8,000,000 Muslims, while today there are about 10,000,000 (the chief reason for this is growth in population among the ten Islamic minorities). At Liberation there were 2,700,000 Catholics; today there are over 3,000,000. Protestants numbered 700,000 in 1949 and are now at 3,000,000. Buddhism (including Lamaism) numbers almost the entire populations of the ethnic minorities of Tibet, Mongolia, and Liao Ning among its adherents. Among the Han race, Buddhism and Daoism still exercise considerable influence at present. Naturally, out of the total population of our country, and especially among the Han race, which accounts for the largest number of people, there are a considerable number who believe in spirits, but the number of those who actually adhere to a religion is not great. If we compare the number of religious believers at the time of Liberation with the present number overall, we will see that overall there has been somewhat of an increase in absolute numbers, but when compared with the growth of the population there has been a decline. But in our appraisal of the religious question, we must reckon fully with its definite complex nature, To sum up, we may say that in old China, during the long feudal period and the more than one hundred years of semicolonial, semifeudal society, all religions were manipulated and controlled by the ruling classes, with extremely negative results. Within China, the Buddhist, Daoist, and Islamic leaderships were mainly controlled by the feudal landowners, feudal lords, and reactionary warlords, as well as the bureaucratic capitalist class. The later foreign colonialist and imperialist forces mainly controlled the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches. After Liberation there was a thorough transformation of the socioeconomic system and a major reform of the religious system, and so the status of religion in China has already undergone a fundamental change. The contradictions of the religious question now belong primarily to the category of contradictions among the people. The religious question, however, will continue to exist over a long period within certain limits, will continue to have a definite mass nature, to be entangled in many areas with the ethnic question, and to be affected by some class-struggle and complex international factors. This question, therefore, continues to be one of great significance which we cannot ignore. The question is this: can we handle this religious question properly as we work toward national stability and ethnic unity, as we develop our international relations while resisting the infiltration of hostile forces from abroad, and as we go on constructing a Socialist civilization with both material and spiritual values? This, then, demands that the Party committees on each level must adopt toward the religious question an attitude in accord with what Lenin said, "Be especially alert," "Be very strict," "Think things through thoroughly." To overestimate the seriousness or complexity of the question and so to panic, or to ignore the existence and complexity of the actual question and so let matters drift, would be equally wrong.

III. The Party's Handling of the Religious Question since Liberation Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, there have been many twists and turns in the Party's work with regard to the religious question. In general, although there were some major errors, after the founding of New China, and for the seventeen years up to the "cultural revolution," the Party's religious work achieved great results under the direction of the correct guiding principles and policies of the Party Central Committee. We did away with imperialist forces within the churches and promoted the correct policy of independent, self-governed, and autonomous churches, as well as the "Three-Self Movement" (self-propagation, self- administration and self-support). The Catholic and Protestant churches ceased to be tools of the imperialist aggressors and became independent and autonomous religious enterprises of Chinese believers. We abolished the special privileges and oppressive exploitative system of feudal religion, attached and exposed those reactionaries and bad elements who hid behind the cloak of religion, and made Buddhists, Daoists, and Muslims break away from the control and manipulation of the reactionary classes. We proclaimed and carried out a policy of freedom of religious belief, enabling the broad masses of religious believers not only to achieve a complete political and economic emancipation alongside each ethnic minority but also enabling them to begin to enjoy the right of freedom of religious belief. We carried out a policy of winning over, uniting with, and educating religious personages, and thus united the broad masses of the patriotic religious personages. We also assisted and supported religious people to seek international friendship and this has had good, positive effects. Since 1937, however, leftist errors gradually grew up in our religious work and progressed even further in the midsixties. During the "cultural revolution" especially, the antirevolutionary Lin Biao-Jiang Qing clique had ulterior motives in making use of these leftist errors, and wantonly trampled upon the scientific theory of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought concerning the religious question. They totally repudiated the Party's correct policy toward religion in effect since the founding of the People's Republic. They basically did away with the work the Party had done on the religious question. They forcibly forbade normal religious activities by the mass of religious believers, as "targets for dictatorship," and fabricated a host of wrongs and injustices which they pinned upon these religious personages. They even misinterpreted some customs and practices of the ethnic minorities as religious superstition, which they then forcibly prohibited. In some places, they even repressed the mass of religious believers, and destroyed ethnic unity. They used violent measures against religion which forced religious movements underground, with the result that they made some headway because of the disorganized state of affairs. A minority of antirevolutionaries and bad elements made use of this situation and, under cover of religious activities, boldly carried out illegal criminal activities, as well as destructive antirevolutionary movements. After the smashing of Jiang Qing's antirevolutionary clique, and especially since the third Plenary Session of the 11th Party Central Committee, the correct guiding principle and policy toward the religious question of our Party was restored step by step. In implementing and carrying out our religious policy, we have opened both Buddhist and Daoist temples, as well as churches and religious sites. We have restored the activities of the patriotic religious associations. We have won over, unified, and educated religious personages. We have strengthened the unity between believers and nonbelievers in each ethnic group. We have righted wrongs and have launched a movement for friendly relations internationally among religious believers as well as resisting infiltration and like doings from hostile religious forces from abroad. In all this, we have undertaken a large number of tasks and have obtained remarkable results. In this new historical period, the Party's and government's basic task in its religious work will be to firmly implement and carry out its policy of freedom of religious belief; to consolidate and expand the patriotic political alliance in each ethnic religious group; to strengthen education in patriotism and Socialism among them, and to bring into play positive elements among them in order to build a modern and powerful Socialist state and complete the great task of unifying the country; and to oppose the hegemonism and strive together to protect and preserve world peace. In order to implement and carry out the Party's religious policy correctly and comprehensively, the main task now at hand is to oppose "leftist" erroneous tendencies. At the same time, we must be on our guard to forestall and overcome the erroneous tendency to just let things slide along. All party members, Party committees on all levels, especially those responsible for religious work, must conscientiously sum up and assimilate the historical experience, positive and negative, of the Party in religious work since the founding of the People's Republic. They must make further progress in their understanding and mastery of the objective law governing the emergence, development, and demise of religion. They should overcome every obstacle and difficulty and resolutely keep the religious policy of the Party on the scientific course laid out for it by Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.

IV. The Party's Present Policy toward Religion The basic policy the Party has adopted toward the religious question is that of respect for and protection of the freedom of religious belief. This is a long-term policy, one which must be continually carried out until that future time when religion will itself disappear. What do we mean by freedom of religious belief? We mean that every citizen has the freedom to believe in religion and also the freedom not to believe in religion. S/he has also the freedom to believe in this religion or that religion. Within a particular religion, s/he has the freedom to believe in this sect or that sect. A person who was previously a nonbeliever has the freedom to become a religious believer, and one who has been a religious believer has the freedom to become a nonbeliever. We Communists are atheists and must unremittingly propagate atheism. Yet at the same time we must understand that it will be fruitless and extremely harmful to use simple coercion in dealing with the people's ideological and spiritual questions--and this includes religious questions. We must further understand that at the present historical stage the difference that exists between the mass of believers and nonbelievers in matters of ideology and belief is relatively secondary. If we then one-sidedly emphasize this difference, even to the point of giving it primary importance--for example, by discriminating against and attacking the mass of religious believers, while neglecting and denying that the basic political and economic welfare of the mass of both religious believers and nonbelievers is the same--then we forget that the Party's basic task is to unite all the people (and this includes the broad mass of believers and nonbelievers alike) in order that all may strive to construct a modern, powerful Socialist state. To behave otherwise would only exacerbate the estrangement between the mass of believers and nonbelievers as well as incite and aggravate religious fanaticism, resulting in serious consequences for our Socialist enterprise. Our Party, therefore, bases its policy of freedom of religious belief on the theory formulated by Marxism-Leninism, and it is the only correct policy genuinely consonant with the people's welfare. Naturally, in the process of implementing and carrying out this policy which emphasizes and guarantees the people's freedom to believe in religion, we must, at the same time, emphasize and guarantee the people's freedom not to believe in religion. These are two indispensable aspects of the same question. Any action which forces a nonbeliever to believe in religion is an infringement of freedom of religious belief, just as is any action which forces a believer not to believe. Both are grave errors and not to be tolerated. The guarantee of freedom of religious belief, far from being a hindrance, is a means of strengthening the Party's efforts to disseminate scientific education as well as to strengthen its propaganda against superstition. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that the crux of the policy of freedom of religious belief is to make the question of religious belief a private matter, one of individual free choice for citizens. The political power in a socialist state can in no way be used to promote any one religion, nor can it be used to forbid any one religion, as long as it is only a question of normal religious beliefs and practices. At the same time, religion will not be permitted to meddle in the administrative or juridical affairs of state, nor to intervene in the schools or public education. It will be absolutely forbidden to force anyone, particularly people under eighteen years of age, to become a member of a church, to become a Buddhist monk or nun, or to go to temples or monasteries to study Buddhist scripture. Religion will not be permitted to recover in any way those special feudal privileges which have been abolished or to return to an exploitative and oppressive religious system. Nor will religion be permitted to make use in any way of religious pretexts to oppose the party's leadership or the socialist system, or to destroy national or ethnic unity. To sum up, the basic starting point and firm foundation for our handling of the religious question and for the implementation of our policy and freedom of religious belief lies in our desire to unite the mass of believers and nonbelievers and enable them to center all their will and strength on the common goal of building a modernized, powerful socialist state. Any action or speech that deviates in the least from this basic line is completely erroneous, and must be firmly resisted and opposed by both Party and people.

V. The Party's Work with Religious Professionals To win over, unite and educate persons in religious circles is primarily the task of religious professionals. It is also the essence of the Party's religious work and most important condition and prerequisite for the implementation of the Party's religious policy. Throughout the country at present, there are about 59,000 professional religious, with affiliation as follows: Buddhist monks and nuns, including lamas about 27,000 Daoist priests and nuns over 2,600 Muslims about 20,000 Catholics about 3,400 Protestants about 5,900 Due to many years of natural attrition, the present number of professional religious has greatly decreased when compared to the number at Liberation. Their class origin, experience, beliefs, and political ideology are quite diverse, but, in brief, we can say that by far the great majority of them are patriotic, law-abiding, and support the socialist system. Only a very small minority oppose the constitution and Socialism to the extent of colluding with foreign antirevolutionaries and other bad elements. Many of these professional religious not only maintain intimate spiritual ties with the mass of religious believers, but have an important influence over the spiritual life of the masses which should not be ignored. Moreover, as they carry out their more formal religious duties, they also perform work which serves the people in many ways and which benefits society. For example, they safeguard Buddhist and Daoist temples and churches and protect historical religious relics, engage in agriculture and afforestation, and carry on the academic study of religion, and so on. Therefore, we must definitely give sufficient attention to all persons in religious circles, but primarily professional religious, uniting them, caring for them, and helping them to make progress. We must unrelentingly yet patiently forward their education in patriotism, upholding the law, supporting socialism, and upholding national and ethnic unity. In the case of Catholics and Protestants, we must strengthen their education in independence and self- government of their churches. We must make appropriate arrangements for the livelihood of these professional religious and conscientiously carry out the pertinent policies. This is especially true regarding the well-known public figures and intellectuals among them, for whom we should speedily implement our policy to supply them with appropriate remuneration. We must pay very close attention to and reexamine those injustices perpetrated against persons in religious circles and among the mass of religious believers which have not yet been redressed. These must be redressed in accordance with the facts, especially those more serious ones which may have grave consequences. These must be firmly grasped and speedily resolved. We must foster a large number of fervent patriots in every religion who accept the leadership of the Party and government, firmly support the Socialist path, and safeguard national and ethnic unity. They should be learned in religious matters and capable of keeping close links with the representatives of the religious masses. Furthermore, we must organize religious persons according to their differing situations and capabilities, respectively, to take part in productive labor, serving society, and in the scholarly study of religion. They should also take part in patriotic political movements and friendly international exchanges. All this is done in order to mobilize the positive elements among religious circles to serve the Socialist modernization enterprise. With regard to those older religious professionals whose term of imprisonment has been completed or whose term at labor reform has ended, as well as those who have not yet been approved to engage in professional religious activities by the religious organizations, each case must be dealt with on its own merits, according to the principle of differentiation. Those who prove to be politically reliable, patriotic, and law-abiding, and who are well-versed in religious matters, can, upon examination and approval by the patriotic religious organizations, be allowed to perform religious duties. As for the rest, they should be provided with alternative means to earn a living. Marxism is incompatible with any theistic world view. But in terms of political action, Marxists and patriotic believers can, indeed must, form a united front in the common effort for Socialist modernization. This united front should become an important constitutive element of the broad patriotic front led by the Party during the Socialist period.

VI. Restoration and Administration of Churches, Temples and Other Religious Buildings To make equitable arrangements for places of worship is a means of implementing the Party's religious policy, and is also an important material condition for the normalization of religious activity. At the time of Liberation, there were about 100,000 places of worship, while at the present time there are about 30,000. This figure includes Buddhist and Daoist temples, churches, and meeting places of simple construction as well as places of worship built by religious believers themselves. The present problem is that we must adopt effective measures, based on each situation, to make equitable arrangements for places of worship. We must systematically and methodically restore a number of temples and churches in large and mid-size cities, at famous historical sites, and in areas in which there is a concentration of religious believers, especially ethnic minority areas. Famous temples and churches of cultural and historical value which enjoy national and international prestige must be progressively restored as far as is possible, according to conditions in each place. But in those places where believers are few and have little influence or where churches and temples have already been demolished, we must work out measures which suit the conditions and do things simply and thriftily according to the principle of what will benefit production and the people's livelihood. After consultation with the mass of religious believers and important persons in religious circles, and with the voluntary support of the believers, we should set aside rather simply constructed places of worship. In the process of restoring places of worship, we must not use the financial resources of either country or collective, outside of government appropriations. And we must particularly guard against the indiscriminate building and repairing of temples in rural villages. We should also direct the voluntary contributions of the mass of religious believers for construction work, so as to build as little as possible. Much less should we go in for large-scale construction lest we consume large sums of money, materials, and manpower and thus obstruct the building up of material and Socialist civilization. Of course we should not demolish existing structures, but fully consult with believers and important persons in religious circles concerning them in order to reach a satisfactory solution based on the actual situation. All normal religious activities held in places so designated, as well as those which, according to religious custom, take place in believers' homes--Buddha worship, scripture chanting, incense burning, prayer, Bible study, preaching, Mass, baptism, initiation as a monk or nun, fasting, celebration of religious festivals, extreme unction, funerals, etc.--are all to be conducted by religious organizations and religious believers themselves, under protection of law and without interference from any quarter. With approval of the responsible government department, temples and churches can sell a limited quantity of religious reading matter, religious articles, and works of religious art. As for Protestants gathering in homes for worship services, in principle this should not be allowed, yet this prohibition should not be too rigidly enforced. Rather, persons in the patriotic religious organizations should make special efforts to persuade the mass of religious believers to make more appropriate arrangements. All places of worship are under the administrative control of the Bureau of Religious Affairs, but the religious organizations and professional religious themselves are responsible for their management. Religious organizations should arrange the scope, frequency, and time of religious services, avoiding interference with the social order and the times set aside for production and labor. No one should go to places of worship to carry on atheist propaganda, nor to incite arguments among the believing masses over the existence of God. In like manner, no religious organization or believer should propagate or preach religion outside places designated for religious services, nor propagate theism, nor hand out religious tracts or other religious reading matter which has not been approved for publication by the responsible government department. In order to ensure further normalization of religious activities, the government should hereafter, in accordance with due process of law, consult fully with representatives from religious circles in order to draw up feasible religious legislation that can be carried out in practice. Major temples and churches famous for their scenic beauty are not only places of worship, but are also cultural facilities of important historical value. Responsible religious organizations and professional religious should be charged with making painstaking efforts to safeguard them by seeing that these monuments receive good care, that the buildings are kept in good repair, and the environment fully protected so that the buildings are kept in good repair, and the environment fully protected so that the surroundings are clean, peaceful, and quiet, suitable for tourism. Under the direction of the responsible government department and religious organizations, the income derived from alms and donations received by these temples and churches can be used mainly for maintenance. A part of this income can even be used as an incentive and reward for professional religious in charge of such places who have been outstanding in this regard.

VII. The Patriotic Religious Organizations To give full play to the function of the patriotic religious organizations is to implement the Party's religious policy and is an important organizational guarantee for the normalization of religious activities. There are a total of eight national patriotic religious organizations, namely: the Chinese Buddhist Association, the Chinese Daoist Association, the Chinese Islamic Association, the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, the Chinese Catholic Religious Affairs Committee, the Chinese Catholic Bishops' Conference, the Chinese Protestant "Three-Self" patriotic Movement, and the China Christian Council. Besides these, there are a number of social groups and local organizations having a religious character. The basic task of these patriotic religious organizations is to assist the Party and the government to implement the policy of freedom of religious belief, to help the broad mass of religious believers and persons in religious circles to continually raise their patriotic and socialist consciousness, to represent the lawful rights and interest of religious circles, to organize normal religious activities, and to manage religious affairs well. All patriotic religious organizations should follow the Party's and government's leadership. Party and government cadres in turn should become adept in supporting and helping religious organizations to solve their own problems. They should not monopolize or do things these organizations should do themselves. Only in this way can we fully develop the positive characteristics of these organizations and allow them to play their proper role and enable them, within constitutional and lawful limits, to voluntarily perform useful work. Thus they can truly become religious groups with a positive influence, and can act as bridges for the Party's and government's work of winning over, uniting with, and educating persons in religious circles. Furthermore, in order to enable each religion to meet expenses under a program of self-support and self-management, we must conscientiously carry out the policy stipulations governing income from house and property rentals. As for the contributions and donations made by believers, there will be no need to interfere as long as they are freely offered and small in quantity. But professional religious should be convinced that private possession of religious income from temples and churches is not allowed and that any action that forces contributions to be made is forbidden.

VIII. Educating a New Generation of Clergy The training and education of the younger generation of patriotic religious personnel in a planned way will have decisive significance for the future image of our country's religious organizations. We should not only continue to win over, unite with, and educate the present generation of persons in religious circles, but we should also help each religious organization set up seminaries to train well new religious personnel. The task of these seminaries is to create a contingent of young religious personnel who, in terms of politics, fervently love their homeland and support the Party's leadership and the Socialist system and who possess sufficient religious knowledge. These seminaries should hold entrance examinations and admit upright, patriotic young people who wish to devote themselves seriously to this religious profession and who have reached a certain level of cultural development. They should not forcibly enroll persons unwilling to undertake this profession or lacking in the necessary cultural educational foundation. Those young professional religious personnel who prove unfitted for this profession should be transferred elsewhere. All these young professional religious should continually heighten their patriotic and Socialist consciousness and make efforts to improve their cultural level and their religious knowledge. They should loyally implement the Party's religious policy. They should show respect to all those upright, patriotic professional religious of the older generation, and conscientiously study and imitate their good qualities. These older and upright patriotic religious professionals should, in turn, cherish these younger patriotic professional religious. In this way the younger ones will become integrated into the patriotic progressive elements of the religious world, and, under the leadership of the Party, will become the mainstay ensuring that religious organizations follow the correct direction in their activities.

IX. Communist Party Members and Religion; Relations with Religious Ethnic Minorities The fact that our Party proclaims and implements a policy of freedom of religious belief does not, of course, mean that Communist Party members can freely believe in religion. The policy of freedom of religious belief is directed toward the citizens of our country; it is not applicable to Party members. Unlike the average citizen, the Party member belongs to a Marxist political party, and there can be no doubt at all that s/he must be an atheist and not a theist. Our Party has clearly stated on many previous occasions: A Communist Party member cannot be a religious believer; s/he cannot take part in religious activities. Any member who persists in going against this proscription should be told to leave the Party. This proscription is altogether correct, and, as far as the Party as a whole is concerned, its implementation should be insisted on in the future. The present question concerns the implementation of this proscription among those ethnic minorities whose people are basically all religious believers. Here, implementation must follow the actual circumstances, and so make use of proper measures, not oversimplifying matters. We must realize that although a considerable number of Communist Party members among these ethnic minorities loyally implement the Party line, do positive work for the Party, and obey its discipline, they cannot completely shake off all religious influence. Party organizations should in no way simply cast these Party members aside, but should patiently and meticulously carry out ideological work while taking measures to develop more fully their positive political activism, helping them gradually to acquire a dialectical and historical materialist worldview and to gradually shake off the fetters of a religious ideology. Obviously, as we go about expanding our membership, we must take great care not to be rushed into recruiting devout religious believers or those with strong religious sentiments. As for that very small number of party members who have shown extreme perversity by not only believing in religion but also joining with those who fan religious fanaticism, even to the point of using this fanaticism to oppose the four basic principles, attack the Party line and its aim and policy, and destroy national integrity and ethnic unity, persons such as these have already completely departed from the standpoint fundamental to Party members. If after having undergone education and criticism, they continue to persist in their erroneous position or feign compliance, then we must resolutely remove them from the Party. If they have committed any criminal acts, then these must be investigated to fix responsibility before the law. Even though those Party members who live at the grass-roots level among these ethnic minorities where the majority believe in religion have already freed themselves from religious belief, yet if they were to refuse to take part in any of those traditional marriage or funeral ceremonies or mass festivals which have some religious significance, then they would find themselves cut off and isolated from the masses. Therefore, in applying those precepts which forbid Party members who live among these ethnic minorities from joining in religious activities, we must act according to concrete circumstances, according to the principle of differentiation in order to allow Party members to continue to maintain close links with the masses. Although many of the traditional marriage and funeral ceremonies and mass festivals among these ethnic minorities have a religious tradition and significance, they have already essentially become merely a part of ethnic custom and tradition. So long as our comrades, especially those living at the grass-roots level, mark clearly the line between ideology and religious belief, then they can show appropriate respect to and compliance with these ethnic customs and traditions in their daily lives. Of course, this does not mean that those customs and traditions which prove harmful to production or the physical and mental health of the masses should not be appropriately reformed in accordance with the desire of the majority of the people. But to lump these ethnic customs and traditions together with religious activities is not right and will be harmful to ethnic unity and to the correct handling of the religious question. All Party members must come to the profound realization that our country is a Socialist state made up of many ethnic minorities. Each minority and each religion is differently situated with regard to this question of the relationship between religion and the ethnic minorities. There are some ethnic minorities in which nearly all the people believe in one particular religion, Islam or Lamaism, for example. Among these peoples, the question of religion and ethnicity is frequently intertwined. But within the Han race, there is basically no relationship between ethnic background and Buddhism, Daoism, Catholicism, or Protestantism. Therefore, we must become adept in distinguishing very concretely the particular situation of each ethnic group and of each religion, and in sizing up the differences and relationships between ethnicity and religion, that we may proceed correctly in our handling of them. We must certainly be vigilant and oppose any use of religious fanaticism to divide our people and any words or actions which damage the unity among our ethnic groups. If our Party cannot with clear mind and firm step master this particular question in the present great struggle as we strive to lead such a great nation of so many ethnic groups as ours forward to become a modern Socialist state, then we shall not be able with any success to unite our peoples to advance together toward this goal.

X. Criminal and Counter-Revolutionary Activities under the Cover of Religion The resolute protection of all normal religious activity suggests, at the same time, a determined crackdown on all criminal and antirevolutionary activities which hide behind the facade of religion, which includes all superstitious practices which fall outside the scope of religion and are injurious to the national welfare as well as to the life and property of the people. All antirevolutionary or other criminal elements who hide behind the facade of religion will be severely punished according to the law. Former professional religious, released upon completion of their term of imprisonment, who return to criminal activities will be punished again in accordance with the law. All banned reactionary secret societies, sorcerers, and witches, without exception, are forbidden to resume their activities. All those who spread fallacies to deceive and who cheat people of their money will, without exception, be severely punished according to the law. Party cadres who profit by these illegal activities will be dealt with all the more severely. Finally, all who make their living by phrenology, fortune telling, and geomancy should be educated, admonished, and helped to earn their living through their own labor and not to engage again in these superstitious practices which only deceive people. Should they not obey, then they should be dealt with according to the law. In dealing according to the law with all antirevolutionary and other criminal elements who lurk within religious ranks, Party committees on each level and pertinent government departments must pay very close attention to cultivating public opinion. They should make use of irrefutable facts to fully expose the way in which these bad elements use religion to further their destructive activities. Furthermore, they should take care to clearly delineate the line dividing normal religious activities from criminal ones, pointing out that cracking down on criminal activities is in no way to attack, but is rather to protect, normal religious activities. Only then can we successfully win over, unite with, and educate the broad mass of religious believers and bring about the normalization of religious activities.

XI. The International Relations of China's Religions Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism, which occupy a very important place among our national religions, are at the same time ranked among the major world religions, and all exercise extensive influence in their societies. Catholicism and Protestantism are widespread in Europe, North America, and Latin America, and other places. Buddhism is strong in Japan and Southeast Asia, while Islam holds sway in several dozen countries in Asia and Africa. Some of these religions are esteemed as state religions in a number of countries. At the present time, contacts with international religious groups are increasing, along with the expansion of our country's other international contacts, a situation which has important significance for extending our country's political influence. But at the same time there are reactionary religious groups abroad, especially the imperialistic ones such as the Vatican and Protestant Foreign-mission societies, who strive to use all possible occasions to carry on their efforts at infiltration "to return to the China mainland." Our policy is to actively develop friendly international religious contacts, but also to firmly resist infiltration by hostile foreign religious forces. According to this policy of the Party, religious persons within our country can, and even should, engage in mutual visits and friendly contacts with religious persons abroad as well as develop academic and cultural exchanges in the religious field. But in all these various contacts, they must firmly adhere to the principle of an independent, self-governing church, and resolutely resist the designs of all reactionary religious forces from abroad who desire to once again gain control over religion in our country. They must determinedly refuse any meddling or interfering in Chinese religious affairs by foreign churches or religious personages, nor must they permit any foreign religious organization (and this includes all groups and their attendant organizations) to use any means to enter our country for missionary work or to secretly introduce and distribute religious literature on a large scale. All religious organizations and individuals must be educated not to make use of any means whatsoever to solicit funds from foreign church organizations, and religious persons and groups in our country as well as other groups and individuals must refuse any subsidy or funds offered by foreign church organizations for religious purposes. As for donations or offerings given in accordance with religious custom by foreign believers, overseas Chinese, or compatriots from Hongkong and Macao to temples and churches within our territory, these may be accepted. But if it is a question of large contributions or offerings, permission must be sought from the provincial, urban, or autonomous-area governments or from the central government department responsible for these matters before any religious body can accept them on its own, even though it can be established that the donor acts purely out of religious fervor with no strings attached. We must be vigilant and pay close attention to hostile religious forces from abroad who set up underground churches and other illegal organizations. We must act resolutely to attack those organizations that carry out destructive espionage under the guise of religion. Of course, in doing so, we must not act rashly, but rather investigate thoroughly, have irrefutable evidence at hand, choose the right moment, and execute the case in accordance with lawful procedures. The new task we now face is that of developing friendly relationships with foreign religious groups while maintaining our policy of independence. The correct guiding principles and policies of the central government and the Party provide the essential basis for doing this type of work well. We should handle the domestic religious question realistically and effectively, strengthen our study of the history of world religion and its present situation, and make efforts to train talented people able to engage in international religious activities. Facts have proven over and over again that if we handle the domestic situation well, then all hostile religious forces from abroad will have little or no opportunity to exploit the situation to their own advantage. Then the international contacts undertaken by religious groups will make smoother and sounder progress and the positive function they should have will be given full play.

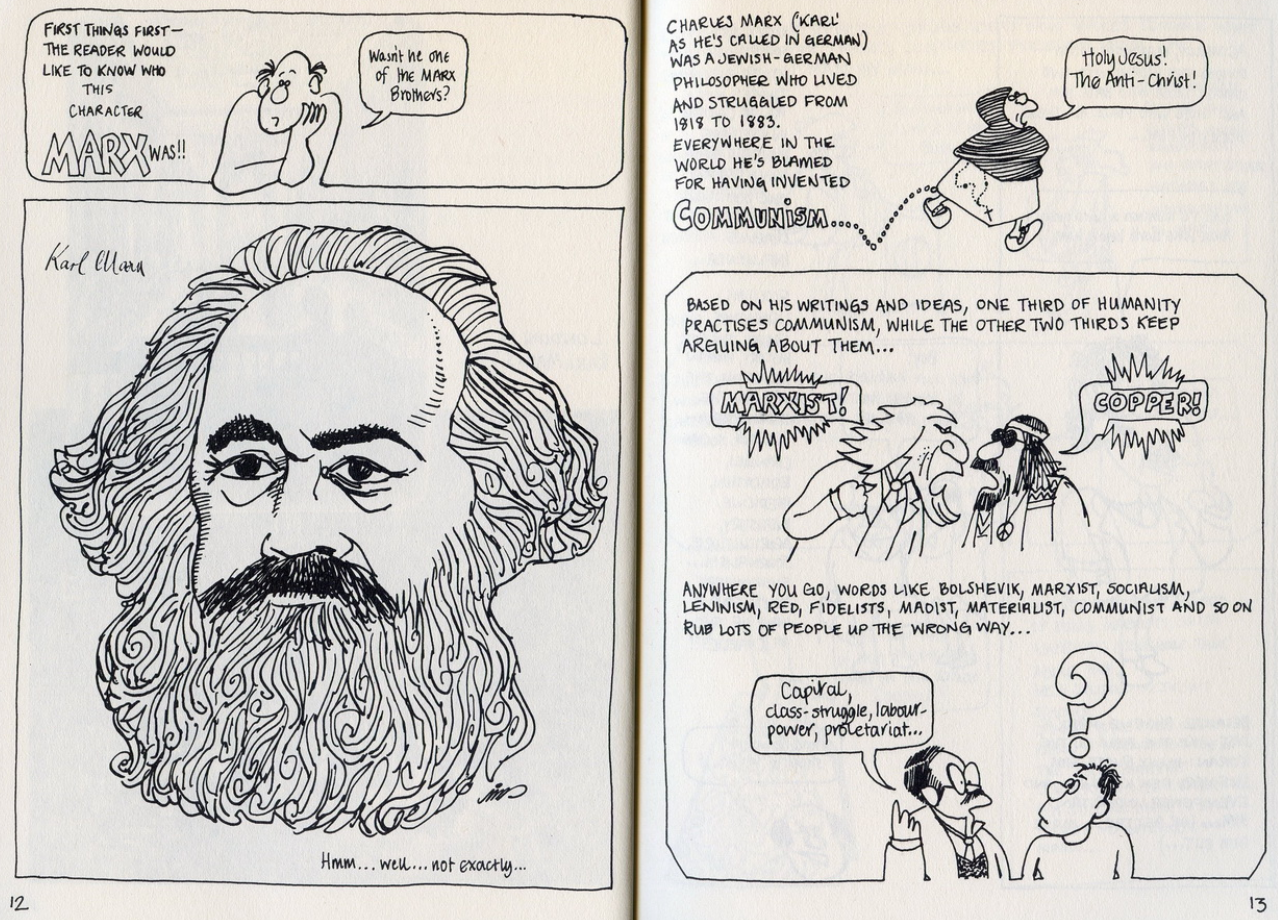

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was living in exile in England when he embarked on an ambitious, multivolume critique of the capitalist system of production. Though only the first volume saw publication in Marx’s lifetime, it would become one of the most consequential books in history. This magnificent new edition of Capital is a translation of Marx for the twenty-first century. It is the first translation into English to be based on the last German edition revised by Marx himself, the only version that can be called authoritative, and it features extensive commentary and annotations by Paul North and Paul Reitter that draw on the latest scholarship and provide invaluable perspective on the book and its complicated legacy. At once precise and boldly readable, this translation captures the momentous scale and sweep of Marx’s thought while recovering the elegance and humor of the original source.

For Marx, our global economic system is relentlessly driven by “value”—to produce it, capture it, trade it, and most of all, to increase it. Lifespans are shortened under the demand for ever-greater value. Days are lengthened, work is intensified, and the division of labor deepens until it leaves two classes, owners and workers, in constant struggle for life and livelihood. In Capital, Marx reveals how value came to tyrannize our world, and how the history of capital is a chronicle of bloodshed, colonization, and enslavement.

With a foreword by Wendy Brown and an afterword by William Clare Roberts, this is a critical edition of Capital for our time, one that faithfully preserves the vitality and directness of Marx’s German prose and renders his ideas newly relevant to modern readers.

Was Wendy Brown really the best choice to write the preface of this?

Did anyone read William Clare Roberts Marx's Inferno?

Am I wrong to be a bit disappointed that it isn't marxian economists working this and is instead critical theory people?

It seems highly regarded and well reviewed. Reading some synopses of it, seems like it would be something I’d be really interested in. However I’m also pretty allergic to philosophy, it usually goes over my head. But then again, a lot of reviewers say Mau keeps things very “practical”?

(Also, being respectful of my Danish comrades with the ø, which I have always liked anyway because I thought it looks cool).

what is the best way to approach it? it seems really interesting but I got confused pretty quick reading it. tried to get quick grasp on it with videos but most were  shit. I think there was a same-titled movie as well?? if so, is it any good?

shit. I think there was a same-titled movie as well?? if so, is it any good?

I hope that this is the right community to ask this question

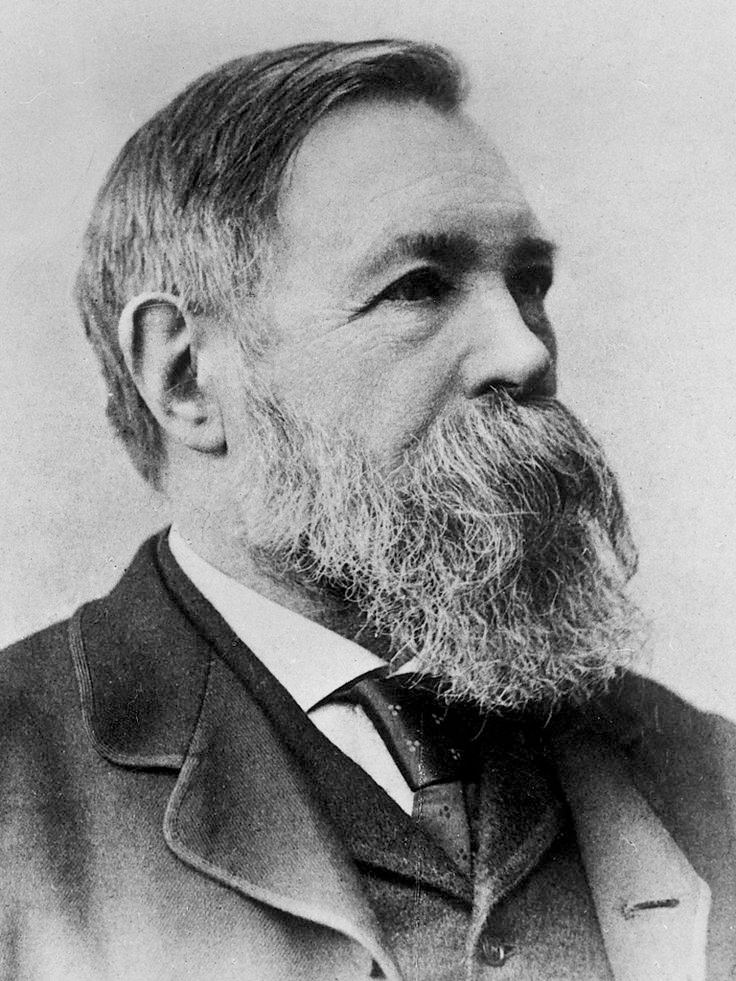

Engels, Frederick, socialist, born in Barmen on Nov. 28, 1820, the son of a well-to-do manufacturer. Took up commerce, but already at an early age began propagating radical and socialist ideas in newspaper articles and speeches. After working for some time as a clerk in Bremen and serving for one year as an army volunteer in Berlin in 1842, he went for two years to Manchester, where his father was co-owner of a cotton mill.

In 1844 he worked for the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher published by Arnold Ruge and Karl Marx in Paris. In 1844 he returned to Barmen and in 1845 addressed communist meetings organised by Moses Hess and Gustav K?ttgen in Elberfeld. Then, until 1848, he lived alternately in Brussels and Paris; in 1846 he joined, with Marx, the secret Communist League, a predecessor of the International, and represented the Paris communities at the two League congresses in London in 1847. On the League's instructions, he wrote, jointly with Marx, the Communist Manifesto addressed to the "working men of all countries", which was published shortly before the February revolution [1848] (a new edition appeared in Leipzig in 1872).

In 1848 and 1849 E. worked in Cologne for the Neue Rheinische Zeitung edited by Marx, and after its suppression he contributed, in 1850, to the Politisch-oekonomische Revue. He witnessed the uprisings in Elberfeld, the Palatinate and Baden and took part in the Baden-Palatinate campaign as aide-de-camp in Willich's volunteer corps. After the suppression of the Baden uprising E. returned as a refugee to England and re-entered his father's firm in Manchester in 1850.

He retired from business in 1869 and has lived in London since 1870. He assisted his friend Marx in providing support for the international labour movement, which arose in 1864, and in carrying on social-democratic propaganda. E. was Secretary for Italy, Spain and Portugal on the General Council of the International. He advocates Marxian communism in opposition to both "petty bourgeois" Proudhonist and nihilistic Bakuninist anarchism. His main work is The Condition of the Working-Class in England (Leipzig, 1845; new edition, Stuttgart, 1892), which, although one-sided, possesses undeniable scientific value. His Anti-Dühring is a polemic of considerable size (2nd ed. Zurich, 1886). E.'s other published works include Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (Stuttgart, 1888), The Origin of the Family Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (4th ed., Berlin, 1891). E. also published Vols 2 and 3 of Karl Marx's Capital and the 3rd and 4th editions of Vol. I, and contributed many articles to the Neue Zeit.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- 💚 Come and talk in the Daily Bloomer Thread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Doesn’t this just quickly become a question of ethics like everything else involving an aggregation of individual actions?

Seems like his new book is very interesting

This post was inspired by a combination of my ignorance regarding the geopolitical implications of currency exchange, a desire to understand what BRICS is and how it works, and comments in this post making fun of Paul Krugman. (https://hexbear.net/post/1040996)

In the comments to the linked post, comrades @emizeko@hexbear.net and @quarrk@hexbear.net discuss an article with an embedded video where economist Michael Hudson rips into some of Krugman's work. (https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2023/05/ny-times-is-wrong-on-dedollarization-economist-michael-hudson-debunks-paul-krugmans-dollar-defense.html)

It's funny, but what I'm really interested in is an idea that Hudson presented. If I understand him correctly he states the following:

If countries conduct trade using American dollars, they have to first acquire these dollars by providing the US treasury with their own currency. This also requires establishing an American bank account. The US then uses that foreign currency to finance military bases/activities in places that require that currency.

The implications, as I understand them, are that you now have an American bank account holding at least some of your assets, and it's vulnerable to being seized by the US government. It also means that a byproduct of using dollars is that the US acquires the means to pay leases, bribes, contractors, etc. to facilitate military dominance all over the globe. Thus, many nations desire to increase their security by moving away from the dollar.

Comrades, help me out. Is this correct? What other basic things are there to know? Is this really why dollar dominance is so important?

I read theory.

I spy some emoji candidates in here too.

Cool explanation of proletarian vs non-proletarian labor, and productive vs non-productive labor, from a classical Marxist view.

Marx’ letter on Russia is of singular significance. Many socialist theoreticians have sought to contest the “legitimacy” of the Russian revolution on the basis of a pedantic construction placed up on the classic Marxian formula: “No social order ever disappears before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have been developed; and new higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society.” Marx’ letter explicitly denies the “supra-historical” validity of this fundamental law of social evolution. That “leap over” bourgeois democracy and into proletarian democracy which Lenin spoke of in 1919, is of a piece with the thoughts expressed in Marx’ letter. The letter, apparently written in 1877, was addressed to Nikolai—on (N.F. Danielson), prominent spokesman of the Russian Populists (Narodniki), economist and publisher of the first Russian translation of Capital. The polemic was directed at N.K. Mikhailovsky, the leading theorist of Russian Populism, who remained a staunch anti-Marxist till his death in 1904. Very little known in Marxian circles, the letter was reproduced in the appendix to the French translation of Nikolai—on’s book on Russian economic development, published in 1902. The three explanatory paragraphs preceding the letter itself are from the pen of the Russian author. The letter is published here for the first time in English, translated from the French in which it was originally written-by Marx. – Ed.

The International Meeting of Communist and Workers' Parties (IMCWP) is an annual conference attended by communist and workers' parties from several countries. It originated in 1998 when the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) invited communist and workers' parties to participate in an annual conference where parties could gather to share their experiences and issue a joint declaration. The most recent and 23rd meeting of the IMCWP is being held in October 2023 in Izmir and hosted by the Communist Party of Turkey (modern).

Organization

The Working Group (WG) of International Meeting of Communist and Workers' Parties (IMCWP) is composed of Communist Parties throughout the world. The task of the working group is to prepare and organize the International Meetings of Communist and Workers' Parties (IMCWPs).

The meetings are held annually, with participants from all around the globe. Additionally, there are occasionally extraordinary meetings such as the meeting in Damascus in September 2009 on "Solidarity with the heroic struggle of the Palestinian people and the other people in Middle East". In December 2009, the communist and workers' parties agreed to the creation of the International Communist Review, which is published annually in English and Spanish and has a website.

The 23rd International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties

The 23rd International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties (IMCWP) begins today in Izmir, Turkey, hosted by the country's Communist Party (TKP).

The Meeting is held between 20-22 October, under the following subject: "The political and ideological battles to confront capitalists and imperialism. The tasks of communists to inform and mobilize the working class, youth, women, and intellectuals in the struggle against exploitation, oppression, imperialist lies and historical revisionism; for the social and democratic rights of workers and peoples; against militarism and war, for peace and socialism."

The contributions from the Communist and Workers' Parties:

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- 💚 Come and talk in the Daily Bloomer Thread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Enver Hoxha, born on this day in 1908, was the communist leader of Albania from 1946 to 1985, leaving behind a complex legacy of feminism and greatly improved access to healthcare and education. Hoxha is also known for having sharp ideological and political disagreements with the Soviet Union and communist Yugoslavia, siding most strongly with and receiving aid from Maoist China.

He was First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania from 1941 until his death in 1985, a member of its Politburo, chairman of the Democratic Front of Albania, and commander-in-chief of the Albanian People's Army. He was the twenty-second prime minister of Albania from 1944 to 1954 and at various times was both foreign minister and defence minister of the country.

Hoxha was born in Ergiri in 1908 and became a grammar school teacher in 1936. Following the Italian invasion of Albania, he joined the Party of Labour of Albania at its creation in 1941 in the Soviet Union.

Before coming into power, Hoxha was a French school teacher and librarian, becoming a communist partisan after fascist Italy invaded Albania in 1939. In March 1943, the first National Conference of the Communist Party elected Hoxha formally as First Secretary.

It was in this position as First Secretary that Hoxha became head of state after the Albanian monarchy was abolished in 1946.

Hoxha declared himself a Marxist–Leninist and strongly admired Soviet Leader Joseph Stalin. The Agrarian Reform Law was passed in August 1945. It confiscated land from beys and large landowners, giving it without compensation to peasants. 52% of all land was owned by large landowners before the law was passed; this declined to 16% after the law's passage.

The State University of Tirana was established in 1957, which was the first of its kind in Albania. The medieval Gjakmarrja (blood feud) was banned. Malaria, the most widespread disease, was successfully fought through advances in health care, the use of DDT, and through the draining of swampland. In 1938 the number of physicians was 1.1 per 10,000 and there was only one hospital bed per 1,000 people. In 1950, while the number of physicians had not increased, there were four times as many hospital beds per head, and health expenditures had risen to 5% of the budget, up from 1% before the war.

Under Hoxha's leadership, the Albanian literacy rate improved from 5-10% in rural areas to more 90%. Hoxha was also a proponent of women's rights, stating "the entire party and country should hurl into the fire and break the neck of anyone who dared trample underfoot the sacred edict of the party on the defense of women's rights". Accordingly, more than 175 times as many women attended secondary schools in 1978 than had done so in 1938.

Relations with Yugoslavia

At this point, relations with Yugoslavia had begun to change. The roots of the change began on 20 October 1944 at the Second Plenary Session of the Communist Party of Albania. The Session considered the problems that the post-independence Albanian government would face. However, the Yugoslav delegation which was led by Velimir Stoinić accused the party of "sectarianism and opportunism" and blamed Hoxha for these errors. He also stressed the view that the Yugoslav Communist partisans spearheaded the Albanian partisan movement.

Tito's position on Albania was that it was too weak to stand on its own and that it would do better as a part of Yugoslavia. Hoxha alleged that Tito had made it his goal to get Albania into Yugoslavia, firstly by creating the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid in 1946. In time, Albania began to feel that the treaty was heavily slanted towards Yugoslav interests, much like the Italian agreements with Albania under Zog that made the nation dependent upon Italy

When Yugoslavia publicly broke with the Soviet Union, Hoxha's support base grew stronger. Then, on 1 July 1948, Tirana called on all Yugoslav technical advisors to leave the country and unilaterally declared all treaties and agreements between the two countries null and void

Relations with the Soviet Union

From 1948 to 1960, $200 million in Soviet aid was given to Albania for technical and infrastructural expansion. Albania was admitted to the Comecon on 22 February 1949 and served as a pro-Soviet force on the Adriatic.

Relations with the Soviet Union remained close until the death of Stalin in March 1953. Under Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's eventual successor, aid was reduced and Albania was encouraged to adopt Khrushchev's specialisation policy. Under it, Albania would develop its agricultural output in order to supply the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries while they would be developing products of their own, which would, in theory, strengthen the Warsaw Pact. However, this also meant that Albanian industrial development, which was stressed heavily by Hoxha, would be hindered

In the years after Stalin's death, Hoxha grew increasingly distressed by the policies of the Soviet leadership and of Khrushchev in particular. China was also disillusioned with Soviet behavior at this time, and Hoxha found common ground with Mao Zedong's criticisms of Moscow. By 1961 Hoxha's attacks on the "revisionist" Soviet leadership had so infuriated Khrushchev that he elected first to terminate Moscow's economic aid to Albania and ultimately to sever diplomatic relations entirely.

Relations with China

At the start of Albania's Third Five-year Plan, China offered Albania a loan of $125 million which would be used to build twenty-five chemical, electrical and metallurgical plants in accordance with the Plan. However, the nation discovered that the task of completing these building projects was difficult, because Albania's relations with its neighbors were poor and because matters were also complicated by the long distance between Albania and China.

The financial aid which China provided to Albania was interest-free and it did not have to be repaid until Albania could afford to do so. China never intervened in Albania's economic output, and Chinese technicians and Albanian workers both worked for the same wages.

During the Cultural Revolution, China entered into a four-year period of relative diplomatic isolation, however, its relations with Albania were positive. Albania's relations with China began to deteriorate on 15 July 1971, when United States President Richard Nixon agreed to visit China in order to meet with Zhou Enlai. Hoxha believed that China had betrayed Albania.

The result of this criticism was a message from the Chinese leadership in 1971 in which it stated that Albania could not depend on an indefinite flow of aid from China. Following Mao's death on 9 September 1976, Hoxha remained optimistic about Sino-Albanian relations, but in August 1977, Hua Guofeng, the new leader of China, stated that Mao's Three Worlds Theory would become official foreign policy. Hoxha viewed this as a way for China to justify having the U.S. as the "secondary enemy" while viewing the Soviet Union as the main one, thus allowing China to trade with the U.S.

On 13 July 1978, China announced that it was cutting off all of its aid to Albania. For the first time in modern history, Albania did not have an ally and it also did not have a major trading partner.

During this period, Albania was the most isolated country in Europe. In 1983, Albania imported goods which were worth $280 million but it exported goods which were worth $290 million, producing a trade surplus of $10 million.

In 1973, Hoxha suffered a heart attack from which he never fully recovered. In increasingly precarious health from the late 1970s onward, he turned most state functions over to Ramiz Alia. Hoxha was succeeded by Ramiz Alia, who oversaw the fall of communism in Albania.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- 💚 Come and talk in the Daily Bloomer Thread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Mentions Samir Amin as well.

Michael Parenti, born on this day in 1933, is a Marxist American political scientist and cultural critic. He has taught at American and international universities and has been a guest lecturer before campus and community audiences.

Michael Parenti was raised by an Italian-American working-class family in the East Harlem neighborhood of New York City. After graduating from high school, Parenti worked for several years. Upon returning to school, he received a BA from the City College of New York, an MA from Brown University and a PhD in political science from Yale University.

For many years Parenti taught political and social science at various institutions of higher learning. Eventually he devoted himself full-time to writing, public speaking, and political activism. He is the author of 20 books and over 300 articles.

Parenti's writings cover a wide range of subjects: U.S. politics, culture, ideology, political economy, imperialism, fascism, communism, democratic socialism, free-market orthodoxies, conservative judicial activism, religion, ancient history, modern history, historiography, repression in academia, news and entertainment media, technology, environmentalism, sexism, racism, Venezuela, the wars in Iraq and Yugoslavia, ethnicity, and his own early life.

His book Democracy for the Few, now in its ninth edition, is a critical analysis of U.S. society, economy, and political institutions and a college-level political science textbook published by Wadsworth Publishing. His book Blackshirts and Reds defended the Soviet Union and socialist states of the 20th century from criticism, arguing that they were morally superior compared to capitalist states, that the problems of the Soviet Union were caused by the Russian Civil War and capitalist interference, and that "Left anti-Communist" and "pure socialist" critics have failed to offer any alternatives to the Soviet Union's "siege socialism"

In 1974, Parenti ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in Vermont as the candidate of the democratic socialist Liberty Union Party; he came in third place, with 7.1% of the vote. Parenti was once a friend of Bernie Sanders, but he later split with Sanders over Sanders's support for the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- 💚 Come and talk in the Daily Bloomer Thread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Indian revolutionary and a major figure in the Indian independence movement of the early Twentieth Century. Singh was active in revolutionary struggle from an early age and he was briefly affiliated with the Mohandas Ghandi’s “Non-Cooperation” movement, although Singh would break with Ghandi’s philosophy of non-violent resistance later in life.

Singh embraced atheism and Marxism-Leninism and integrated these key components into his philosophy of revolutionary struggle. Under his leadership, the Kirti Kissan Party was renamed the Hindustan Socialist Republican Organization. As Singh and his organization rose to new prominence in the Indian independence movement, they became the focus of public criticism from Ghandi himself, who disagreed with their belief that violence was a necessary and vital component of revolutionary struggle.

Singh’s secularism was perhaps his most important contribution to the socialist and independence struggles. During those turbulent times, British Imperialism used every tactic to create antagonism among the different religions of India, especially between Hindus and Muslims. The Sanghatan and Shuddi Movements among Hindus; and tableegh and many sectarian movements in Muslims bear witness to the effects of this tactic. Bhagat Singh removed his beard which was a violation of Sikh religion, because he did not want to create before the public the image of a ‘Sikh’ freedom fighter. Nor did he want to be held up as a hero by the followers of this religion. He wanted to teach the people that British Imperialism was their common enemy and they must be united against it to win freedom.

On April 8, 1924, Baghat Singh and his compatriot B. K. Dutt hurled two bombs on to the floor of the Central Delhi Hall in New Delhi. The bombs were tossed away from individuals so as not to harm anyone and, in fact, no one was harmed in the ensuing explosions. Following the explosions, Singh and Dutt showered the hall with copies of a leaflet that later was to be known as “The Red Pamphlet.” The pamphlet began with a passage which was to become legendary in the Indian revolutionary struggle:

“It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear, with these immortal words uttered on a similar occasion by Vaillant, a French anarchist martyr, do we strongly justify this action of ours.”

Singh and Dutt concluded the pamphlet with the phrase “Long Live the Revolution!” This phrase (translated from “Inquilab Zindabad!” became one of the most enduring slogans of the Indian Independence Movement.

Singh and Dutt turned themselves in following the bombing incident. Following the trial, they were sentenced to “transportation for life” and while imprisoned, Singh and Dutt became outspoken critics of the Indian penal system, embarking on hunger strikes and engaging in agitation and propaganda from within the confines of the prison. Shortly after the commencement of his prison sentence, Singh was implicated in the 1928 death of a Deputy Police Superintendent. Singh acknowledged involvement in the death and he was executed by hanging on 23 March 1931.

Bhagat Singh is widely hailed as a martyr as a result of his execution at the hands of oppressors and, as such, he is often referred to as “Shaheed (Martyr) Bhagat Singh.”

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

I recently discovered these two terms, Fordism and Post-Fordism. I have recently been on the David Graeber tip,[ , re-reading Bullshit Jobs and some of his other essays on the Anarchist library. Dude was and still is 420% right about modern work and how/why it sucks, however I didn't really have that sort of deeper theory based framework of understanding why it sucks and how it came to suck so much.

, re-reading Bullshit Jobs and some of his other essays on the Anarchist library. Dude was and still is 420% right about modern work and how/why it sucks, however I didn't really have that sort of deeper theory based framework of understanding why it sucks and how it came to suck so much.

I'm generally anti-work as the next leftie. However, I do think there is a lot of work that needs to be done and we should all do, but we should all not have to do it all the time for all of our lives. In general most jobs that need to be done can be done collectively or through a shared and equitable fashion. That said 93.7% of modern jobs don't needs to exist and the remain 6.3% of jobs could be radically re-imagined to be fairer and better for the worker.

Reading about Fordism and Post-Fordism I'm really understanding that capital-M "Management" in just about every industry all want to see a workforce strongly resembles that of a factory churning out repeatable products. Everything a process, that can be measured, and repeated, and traced, even the works themselves become a collection processes. I'm also listening to a podcast on Gramsci  and learning more about a theorist I never knew about.

and learning more about a theorist I never knew about.

While I knew of this sort of sentiment before I didn't really parse it through a Marxist lens until reading about it more thoroughly and experiencing it now that I'm "moving up" in my current bland MEGACORP job. I'm experiencing people around me trying to internalize this ideology in a weird modern way, like it's somehow "progressive™ ® © " to want to become a better cog. To self optimize your cog-y-ness, and to want to hyper specialize your cog-y-ness. The worst part of it all is that it's seen as "self-actualizing" and generally a good thing to want to turn yourself in to the cog. The manufactured desire of you wanting to debase yourself for your boss is just vile to me.