Welcome to baby Marxist rehabilitation camp.

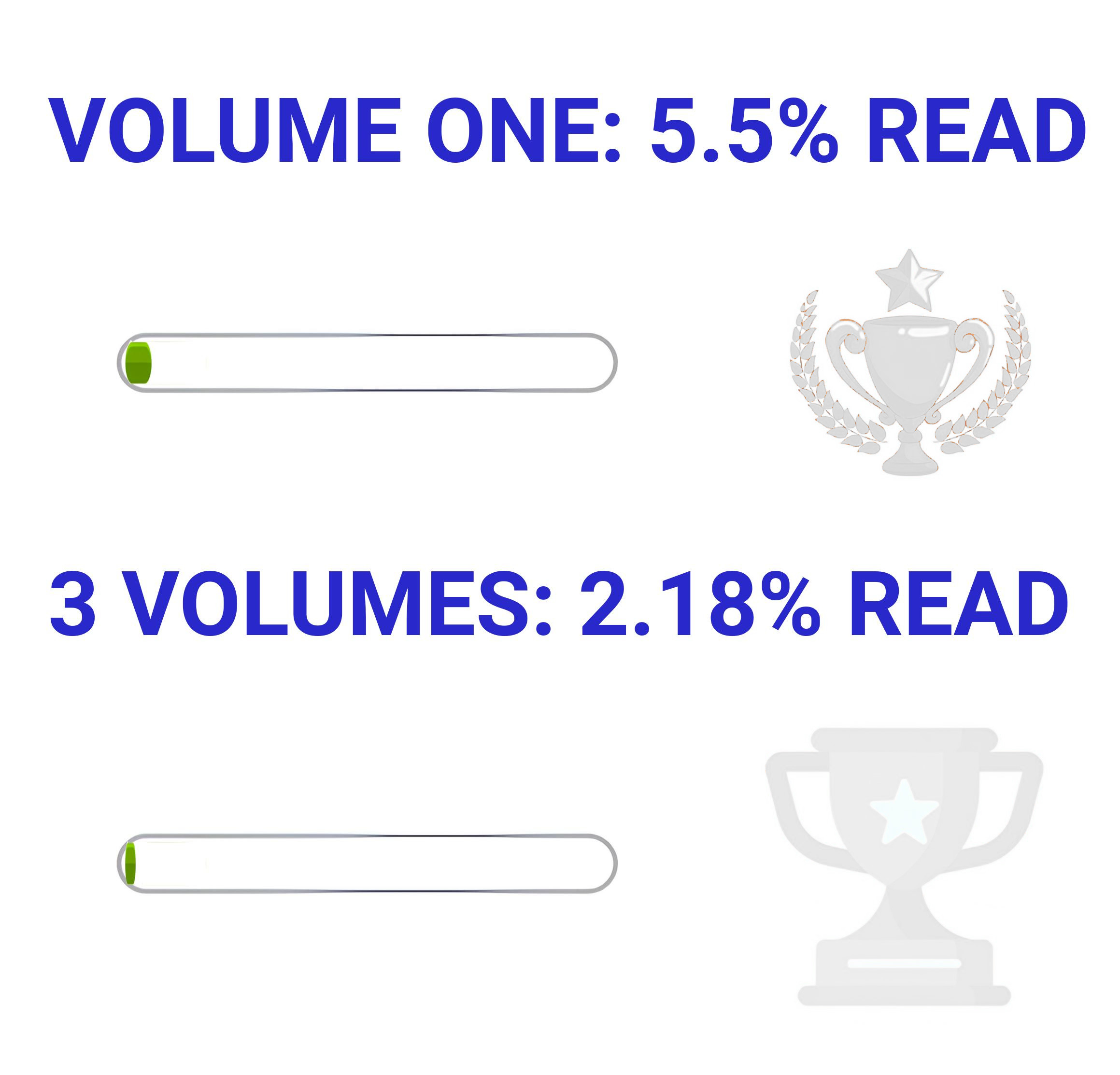

We are reading Volumes 1, 2, and 3 in one year. (Volume IV, often published under the title Theories of Surplus Value, will not be included in this particular reading club, but comrades are encouraged to do other solo and collaborative reading.) This bookclub will repeat yearly until communism is achieved.

The three volumes in a year works out to about 6½ pages a day for a year, 46⅔ pages a week.

I'll post the readings at the start of each week and @mention anybody interested. Let me know if you want to be added or removed.

We currently have 58 members!!! I expect a certain drop-off rate, but I'll be thrilled if a dozen or couple dozen read it.

If you've made it this far, you've already read ¹⁄₁₈ of Volume I. The first three weeks are the hardest, after that it'll be quite easy, and only requires 20 minutes a day (endurance is key).

Just joining us? It'll take you about 2-3 hours to catch up to where the group is. You can do that on one long bus ride.

Archives: Week 1

Week 2, Jan 8-14, we are reading Volume 1, Chapter 2 'The Process of Exchange', PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 3, Section 1 'The Measure of Values' PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 3, Section 2 'The Means of Circulation'

In other words, aim to get up to the heading '3. Money' by Jan 14

Discuss the week's reading in the comments.

Use any translation/edition you like. Marxists.org has the Moore and Aveling translation in various file formats including epub and PDF: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Ben Fowkes translation, PDF: http://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=9C4A100BD61BB2DB9BE26773E4DBC5D

AernaLingus says: I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn't have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you're a bit paranoid (can't blame ya) and don't mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

Resources

(These are not expected reading, these are here to help you if you so choose)

-

Harvey's guide to reading it: https://www.davidharvey.org/media/Intro_A_Companion_to_Marxs_Capital.pdf

-

A University of Warwick guide to reading it: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/worldlitworldsystems/hotr.marxs_capital.untilp72.pdf

-

Reading Capital with Comrades: A Liberation School podcast series - https://www.liberationschool.org/reading-capital-with-comrades-podcast/

When he says "Owen's 'labour money', for instance, is no more 'money' than a theatre ticket is", I don't see how that's a bad thing.

It can be a good thing because that implies it does not recirculate, and won't lead to the accumulation of wealth.

If the tokens "are money" whatever that means, it means the person getting them as wages can use them to do bourgeois things.

I think this is a good conversation to have because it gets to the heart of what Marx thinks about money theoretically in Capital. And while I do think Capital contains the words to form the same conclusion as Marx, I think it's just vague enough to lead to various interpretations. So it's worth looking at his other texts for this question. Like I mentioned in a separate comment, I think Grundrisse is the place he most directly discusses the question of labor money, which can be summarized by this quote:

Grundrisse quote

The question is not whether labor money would be good, it's whether it is possible on the basis of commodity production, and whether it would actually lead to socialism. For Marx, the answer is no to those two questions.

To identify money as the cause of capitalism is to say that capitalism arises from circulation, in fact only a form of circulation, and not from the very conditions of production as distributed among individual producers as private property. Ideas and forms do not cause changes in the material basis. It is the reverse. The material basis produces ideas and forms.

The idea of labor money springs from a conception of money as a mere tool, an idea that was invented for convenience but is not essential to capitalism. What Marx is trying to show in chapters 1-3 is that you cannot have capitalism without money. Money is as essential as value to commodity production and arises in proportion as value arises.

Lastly I'll leave a bit from this week's reading:

Quote from Capital chapter 2

From here I think we have a new perspective on chapter 1 section 3C, The General Form of Value. In that section it can seem that the idea to flip around the expanded form is just an idea. But my read is that it is something that happens automatically in practice, people "acted and transacted before they thought." To understand why, we have to consider what the purpose of exchange is: it is to realize the validity of private labor as social labor. If people are producing privately, then it becomes obscured the fact that they are at one and the same time also producing socially, as part of a social division of labor. An individual exchange of two use values does not in itself establish the two concrete labors as general social labor, as they are only two specific commodities. So money functions not just as a convenience of circulation, but as a means to express the general social validity of the labor in each commodity, which is its value.

In a socialist society without private property, then it can be possible for society to say that if you work for 1 hour, you can retrieve whatever that society directly calculates as being worth 1 hour. That makes it directly social labor, or "immediately" social, immediate as in not mediated indirectly through a form like money, or through generalized commodity exchange.

Edited formatting for the quotes

Additional really helpful section in Theories of Surplus Value

TSV quote (bold added to emphasize money as necessary and essential)