Welcome to baby Marxist rehabilitation camp.

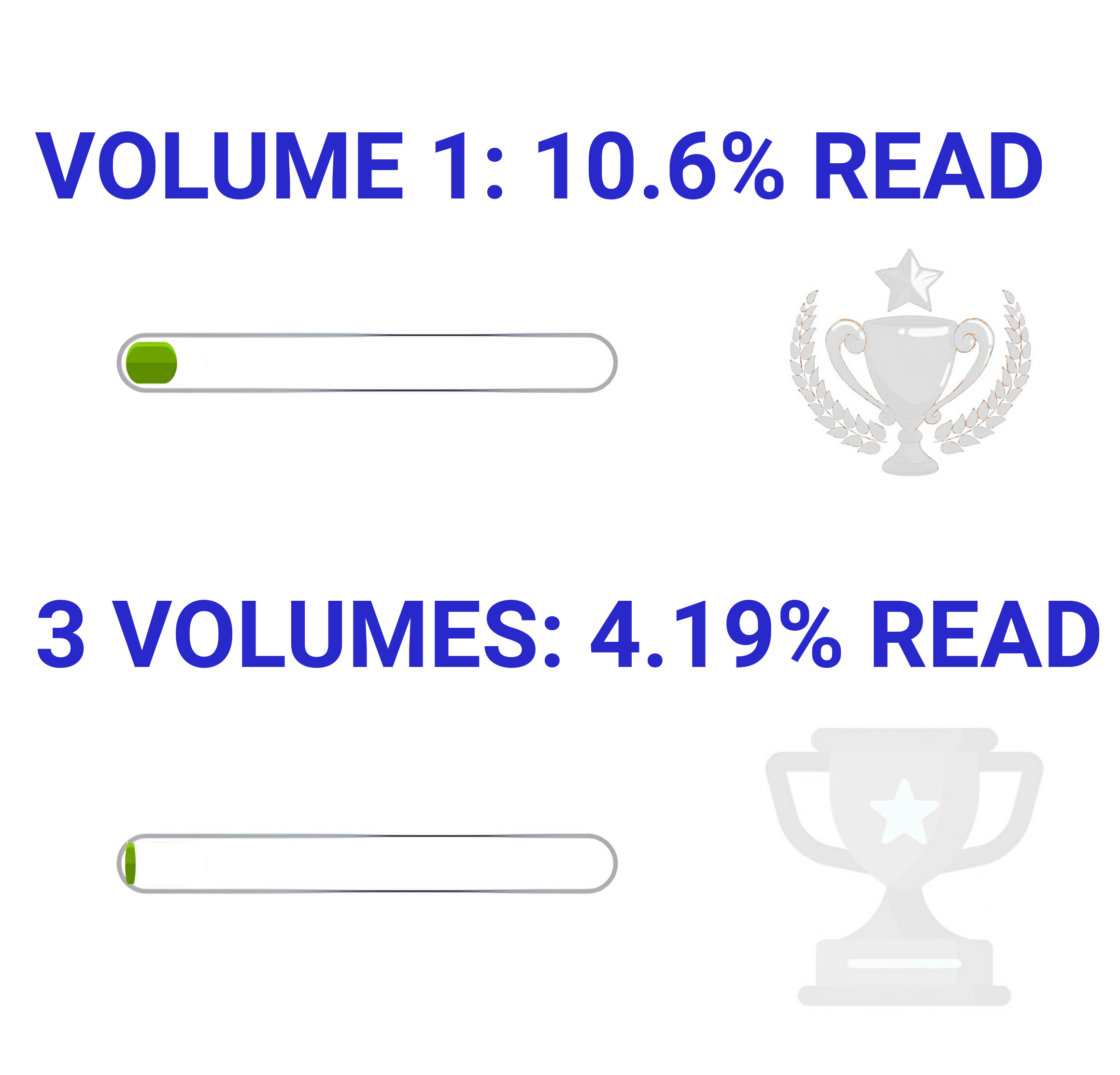

We are reading Volumes 1, 2, and 3 in one year. (Volume IV, often published under the title Theories of Surplus Value, will not be included in this particular reading club, but comrades are encouraged to do other solo and collaborative reading.) This bookclub will repeat yearly until communism is achieved.

The three volumes in a year works out to about 6½ pages a day for a year, 46⅔ pages a week.

I'll post the readings at the start of each week and @mention anybody interested. Let me know if you want to be added or removed.

Congratulations to those who've made it this far. We are almost finished the first three chapters, which are said to be the hardest. So far we have just been feeling it out, now is when we start to find our stride. Remember to be methodical and remember that endurance is key.

Just joining us? It'll take you about 4-5 hours to catch up to where the group is.

Week 3, Jan 5-21, we are reading Volume 1, Chapter 3 Section 3 'Money', PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 4 'The General Formula for Capital', PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 5 'Contradictions in the General Formula'

Discuss the week's reading in the comments.

Use any translation/edition you like. Marxists.org has the Moore and Aveling translation in various file formats including epub and PDF: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Ben Fowkes translation, PDF: http://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=9C4A100BD61BB2DB9BE26773E4DBC5D

AernaLingus says: I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn't have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you're a bit paranoid (can't blame ya) and don't mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

Resources

(These are not expected reading, these are here to help you if you so choose)

-

Harvey's guide to reading it: https://www.davidharvey.org/media/Intro_A_Companion_to_Marxs_Capital.pdf

-

A University of Warwick guide to reading it: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/worldlitworldsystems/hotr.marxs_capital.untilp72.pdf

-

Reading Capital with Comrades: A Liberation School podcast series - https://www.liberationschool.org/reading-capital-with-comrades-podcast/

I feel like I'm getting a little bit hung up on value vs exchange value (which I guess is kinda like price). And gold. I'm happy enough to move along with value defined as "socially necessary labour" (or SNL+naturally occurring+chance stuff? idk) and exchange value as "price, give or take", but I feel like the arguments kinda got glossed over. I did rush last week's reading because I was very busy (and then sick). I can just hear the campus libertarian in the back of my head saying "ho ho ho labour value". Ultimately, SNL compared to the SNL mass of all commodities in society is what creates exchange value (or LT compared to SNness and desire?), and SNL is a combination of technology, training, and ability of each participant in a society.

I did a forklift certification today and yesterday, and I feel like I'm doubting some of my classmates ability to do these chapters. Maybe if they were really invested in it?

No, no, no. "Value" is a shorter way of saying "exchange value"

The duality is: [Use-value] vs [Value], or, said differently: [Use-value] vs [Exchange-Value]

There's no conceptual duality of: ~~[Value] vs [Exchange-Value]~~, put that out of your mind.

This seems about right so far. Value is like the "true" or "proper" price, determined by embedded labour. The difference between price and value will be talked about more later; actually Marx hasn't really discussed price yet. But for now, just think of value as the proper price. (Like in Ch.5 in this week's reading: "It is true that commodities may be sold at prices which diverge from their values, but this divergence appears as an infringement of the laws governing the exchange of commodities.")

Page numbers from Fowkes penguin translation, emphasis is mine

It isn't a duality, it's a series of reflections (commodity-value -> exchange-value -> price). Commodity-value is the socially necessary labour in a commodity, exchange-value is it's reflection in another commodity and price is that exchange value in money. All three of them can differ from each other to some extent (particularly 'commodity-value/value', which can never be actually observed or measured except as seen in its reflection/likeness, exchange-value and the ). All three of these things' ability to diverge from each other is necessary for the capitalist system to function on its laws of averages. Exchange-value is the equivalent of a commodity's commodity-value in another commodity (e.g. the value of a shoe in ounces of gold). Price is a representation of the ratio in which a commodity can be exchanged for money.

Also very important to note (for feminism/ecological/ableism/etc critique) that Marx is laying out the standards of capitalist value, which doesn't necessarily represent the actual work/labour exerted on a given thing, e.g. doesn't represent the labour required to produce a forest cut down.

I agree with you that there is no duality, but there is a distinction.

I think you are referring to this bit from chapter 1?:

Exchange-value is a value-form or form of value. The difference is that use-value/value are an internal opposition whereas use-value/exchange-value are an external opposition, because in the latter case they are mere forms of appearance of an internal content.

It sounds like a pedantic point, but distinction between form and content occurs in other places in Capital. Value takes on various forms through the productive process, and these forms are important to study, not just value in the abstract. Money as a form of value has peculiar features and functions that distinguish it from commodities, which are themselves forms of value. And yet was also important for Marx to unify the various forms of surplus value under one general theory of surplus value; he wrote to Engels that one of the best points in Capital is "the treatment of surplus value independently of its particular forms as profits, interest, ground rent, etc."

And while value is a content which takes various forms, value is itself a form, whose content is social abstract labor; or in other words, value is a form of the social relations of commodity production.

Sections 4 and 5 in the appendix on the value-form elaborate a bit on the distinction between exchange-value and value:

For a hopefully short answer, exchange value is only the ratio of some property of two commodities, commodity a : commodity b. What is that property being compared? Value.

Commodities don't "have" exchange value, they "have" value. But in our day to day lives, we don't see value, we only see exchange value. The exchange value is what spills the beans that there is some property of commodities known as value.

I would like to say here that Marx is not thinking in terms of desire or supply and demand at all when he talks about value or the magnitude of value. The magnitude of value is exactly one value at any moment in time, and it is the socially necessary labor time required to produce the commodity. Any notion of desire affecting exchange value is the effect of later neoclassical economics seeping into our understanding of Marx. If this leaves you confused, remember that we are not yet talking about prices. Value is something different than price.

Value is measured by socially necessary labor time / SNLT. Labor time, because in exchange the different concrete labors are abstracted into an undifferentiated labor time. Socially necessary, because value expresses not just two commodities in relation to each other, but the entire universe of commodities in relation with the aggregate social product of society. So these abstract labor units represent units of a total mass of labor representing the productive capacity of society. (This is where the necromancy comes in - this is all dead labor, labor which has already finished!)

The fact that commodities have value, a property reflecting the social connection of all commodities to each other, and therefore the labor of society, is what Marx is talking about in the end of ch 1 on the fetishism of commodities. He's just saying it's a very odd thing about commodities that appears natural, but at the same time reflects a social fact. And it's not just imagined, but something which exists quasi-objectively.

*note I'm pretty behind on reading (just finished ch.1) but it's not my first pass so idk

I feel like adding the "socially necessary"ness adds an element of desire in that a production run of RBG funko pops ceases to have value once the social uses are filled.

But also having trouble with the jump from different "values" to just one value which is exchange value (?). There was like one line but it didn't feel illuminating.

Thanks for the help with definitions though

Yeah, there's definitely a piece that the use value of a commodity has to be needed by someone. But if a product of labor fails to do this, then that means it fails to be transformed from a simple object into a commodity at all. So we can take it as a given that all commodities are useful to someone, but this is a qualitative fact that doesn't enter into the quantitative determination of value.

Not talking about price here, which is of course subject to lots of things like supply and demand and let's say subjective desire. Value, on the other hand, is a constant and objective quantity at a given moment. "Socially necessary" is objective, not subjective, which comes out of the fact that value is measured not only in labor time, but in abstract labor time in a society where the majority of goods are produced for sale.

Value being counted in units of labor time comes from the analysis that labors of different kinds are abstracted in exchange.

Value being further qualified as socially necessary labor comes from the fact that the entire society labors in order to produce commodities, and therefore the value of each commodity is counted in average labor units of the whole.

from ch 1

Maybe the earlier part of my comment helps with this question? Also clarification on the (?), the jump is instead from different concrete labors (sewing, shoemaking, programming) to just one kind of labor, abstract labor.

Before a product of labor is sold, it's not really a commodity, because its production hasn't been validated as being socially necessary. At this point, it's just a simple object, which required some concrete labor to produce it. The concrete labor might have taken 10 hours, 12 hours, 300 hours, etc, depending on things like the skill of the producer. At this point unrelated to the social average time needed to produce it.

Now the product of labor wants to participate in exchange, but it has a problem. Equating apple = hat is incoherent because they are different kinds. But we know in the real world, this kind of equation is done every day. So the product of labor makes a deal with the devil. An apple can exchange for a hat, but only if both the apple and hat forget everything about themselves, except the fact that human labor in general produced them. Then they can be compared as abstract labor = abstract labor. Foreshadowing a bit, concrete and abstract labor as concepts are in tension, as the commodity producer will be compelled to reduce the concrete labor as much as possible. This is because in exchange, their commodity is only worth as much as the quantity of abstract labor.

It turns out that, value doesn't really care what physical embodiment it has. It's like a demon that possesses the body of whichever commodity it can, but it must possess some body. So some kind of concrete labor is necessary, but in the end, it turns out that the same one human labor performs two kinds of labor simultaneously: concrete labor, and abstract labor. They both have different quantities: concrete labor is measured literally by how long it took to do the specific kind of labor. Abstract labor is measured socially, by how much time "should" have been spent to produce the object, in the current society with the current level of technological development etc. The abstract labor is what is compared in exchange, not the concrete labor. Comparing the concrete labor is the logical fallacy which produces the mud pie argument.

I will read this comment a few times

no prob, I didn't intend the post to get that long, it just happened lol

I learn a lot through discussion, but also tend to get defensive easily. I hope that hasn't come through here

Not at all, I'm using your questions like homework to check if I understood it

Oh, and he also mentioned that some sources of value are from rare or valuable land (rivers, fertile ground, quarries I guess). My assumption is that it is rolled into SNL as it requires labour to work, there's just an upper limit on the production of, say, iron based on the accessibility of iron ore and the social necessity of iron ore, which is determined by exchange etc etc? A society where there are just lumps of iron lying around probably expends very little labour extracting iron ore.

Do you recall what section that part on value from rare/valuable land was from? I'm still behind in my reading and it's been a while. I remember this part from ch 1:

And then for sure in Volume 3 there is a long discussion on differing qualities of land, but this fits into the rent part of the analysis (it's later and we are not there yet in Marx's build-up of concepts). Just to foreshadow that part, Marx describes a differential of rents based on how good the land is and how much value can be produced with it.

To me, as per the ch 1 quote above, Marx is describing a precondition for producing a use-value with concrete labor. Remember that producing a use-value is an inescapable requirement of also producing a value, since value must have some bodily form to possess. So Marx is making this simple trans-historical statement not only about labor under capitalism, but all human labor: in order for humans to make things, we need to find existing material things and alter them with our labor.

It's kind of mind-bending, but several parts of the argumentation in these chapters is starting from an end result, and then describing what things must have been necessary to reach this point. Rather than starting with ingredients and describing a recipe how to make a commodity, Marx takes the commodity and describes the preconditions necessary to make it. So what looks like he's making wild assumptions ("why can he assume it's socially necessary labor?"), is actually a result of this direction of the analysis.

For example, this is the direction of the first chapter: Wealth in present society takes the form of commodities. To have a commodity, you need a use-value which was exchanged for some other use-value. Ok, what is a use-value? Something which is the product of a definite type of labor, using physical matter found in the world. Ok, it's exchanged? Then it must have been socially necessary. He doesn't make moral or value judgments about WHY it's socially necessary, he is simply stating the fact that it was already exchanged, therefore socially necessary.

Contrast this with a "bottom-up" approach, trying to design a commodity by first starting with concrete labor. A baker bakes, a barber cuts hair, and a carpenter makes furniture. To try to back into Marx's analysis, you have to try to explain how the baker 1) is performing socially necessary labor 2) is performing labor in the abstract, not his specific labor 3) calculates the "value" in his product during exchange. This is basically a problem that classical economists ran into (and to whom Marx is responding), because they were trying to give all sorts of definitions for how value is calculated, but it's exactly backwards compared to how Marx is analyzing it. The problem is that the classical economists are starting the analysis already making the assumption that value exists. But this has the problem of making value into some ahistorical phenomenon, and therefore missing the entire history of capitalism and making it impossible to describe how capitalism develops and changes.

It was one line somewhere, but I'm not finding it. I did find a paragraph bouncing some examples around in chapter 1. Disregard, for now. ATM, I'm falling behind on readings and I haven't even started semester yet :(

Right there with ya, just take it easy and remember the goal is to read it, not for it to stress us out! I have no chance of keeping up because of work