At the time of his death in 1927, he was lauded as “one of the most indicted and imprisoned workers” in the history of the American labor movement. Yet today, few know the name Charles Emil Ruthenberg. When he passed away suddenly at the age of 44, he cheated a Michigan prison of its next inmate and left a young Communist Party USA—then called the Workers (Communist) Party—in mourning for its first general secretary.

Socialist agitator

Born the son of a Cleveland longshoreman in 1882, Ruthenberg’s formal education ended when he was 16, but he continued studying on his own, becoming part of the pool of “working-class intellectuals.” He worked a series of jobs, including in a picture frame factory, before eventually scoring a position in the business department of a book company. He developed his administrative and executive abilities there during the day and continued his self-education at night.

Seeing the class struggle play out on the job, he became more and more disillusioned with the social and economic system of capitalism. Initially preparing for a life as a minister, Ruthenberg traded the Bible for Capital, borrowed from his local library branch. When asked by a prosecutor years later how he had been converted to socialism, he answered: “Through the Cleveland Public Library.”

By 1909, when he was 27, Ruthenberg had officially joined the Socialist Party. A year later, he was the party’s candidate for Ohio state treasurer, running on a platform that called for unemployment insurance—several decades before that reform was eventually won. 60,000 people cast their ballots for him. Two years later, he was the candidate for Cleveland mayor, part of a wave of Socialist campaigns that made Ohio the country’s first “Red State,” although that designation meant something very different than it does today.

He quickly became an outspoken figure on the Socialist Party’s left wing, known for his uncompromising attitude against the imperialist war looming in Europe. When the U.S. finally entered the conflict in 1917, Ruthenberg led the campaign for an anti-war resolution at the Socialist Party’s National Emergency Convention in St. Louis. He and other left-wingers were determined that their party not follow the example of the European socialist parties supporting the war.

In June, he was arrested, along with Alfred Wagenknecht and Ohio SP organizer Charles Baker, for obstructing the military draft. A swift conviction in November—the same month as the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia—sent them all to prison for a year. He and his comrades began serving their term in January 1918. From that time right up until his death, Ruthenberg was either in prison or facing imprisonment.

Emerging from the Canton workhouse just as the war was ending, Ruthenberg returned immediately to work. Support for the left wing of the party was consolidating among the membership, driven by dissatisfaction with the lukewarm way the party leadership had met the issue of imperialist war, its half-hearted embrace of the workers’ revolution in Russia, its refusal to join the new Communist International, and its failure to support efforts to build industrial labor unions.

The left wing, with Ruthenberg leading the charge, carried on an intense campaign to shift the party’s direction. In elections for the executive, they took 12 out of 15 seats. The old leadership refused to honor the results, however, and initiated a purge of all the left-led state parties and foreign language federations, which together represented the vast majority of the party membership. Through its bureaucratic maneuvers, the right-wing leadership effectively split the Socialist Party.

Communist founder

Ruthenberg was fresh out of jail once again after having charges against him in connection with Cleveland’s 1919 May Day parade dismissed when the break with the Socialist leadership was made official.

Though united in their opposition to what they saw as the “opportunism” of the Socialist Party executive committee, Ruthenberg and the other left-wingers were divided as to how they should proceed. The bulk of the left wing, with Ruthenberg and Fraina at their head, prepared for the founding of a new party—a communist party. They set Sept. 1 as the date to establish the new group.

But a group led by Reed and Wagenknecht insisted on staging a raid of the upcoming Socialist convention in Chicago, scheduled for the end of August, to take the seats they’d been elected to. It was a foregone conclusion that they’d be denied credentials, and so they rented a room downstairs from the official meeting, anticipating they’d need a place to set up their own party.

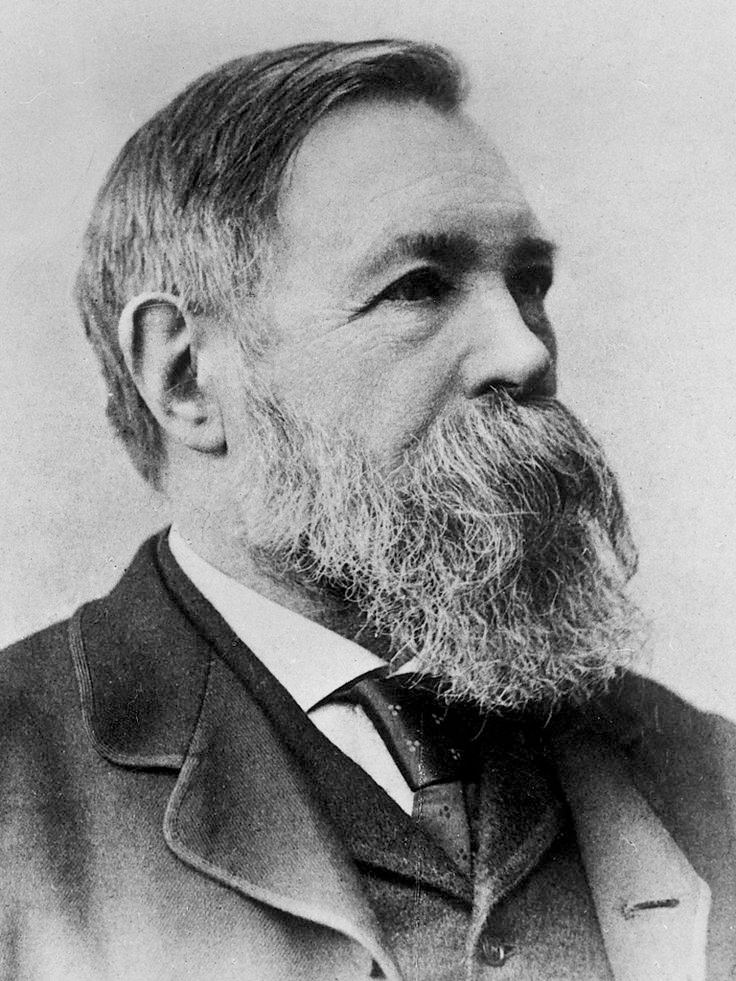

At noon the next day, the founding convention of the Communist Party of America opened on Chicago’s Blue Island Avenue at the headquarters of the Russian Socialist Federation. The meeting hall was decked out in red banners bearing revolutionary slogans. Portraits of Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky hung above the stage.

Just as the meeting was about to open, the Chicago Police Red Squad busted into the hall, and detectives immediately began tearing down and destroying all the flags and floral decorations. Photographers rushed in to take pictures of everybody. The delegates stared at the police, and then a brass band struck up the “Internationale” and everyone started to sing and cheer.

After the excitement died down a bit, Louis Fraina made the opening keynote with the following words: “We now end, once and for all, all factional disputes. We are at an end with bickering. We are at an end with controversy.”

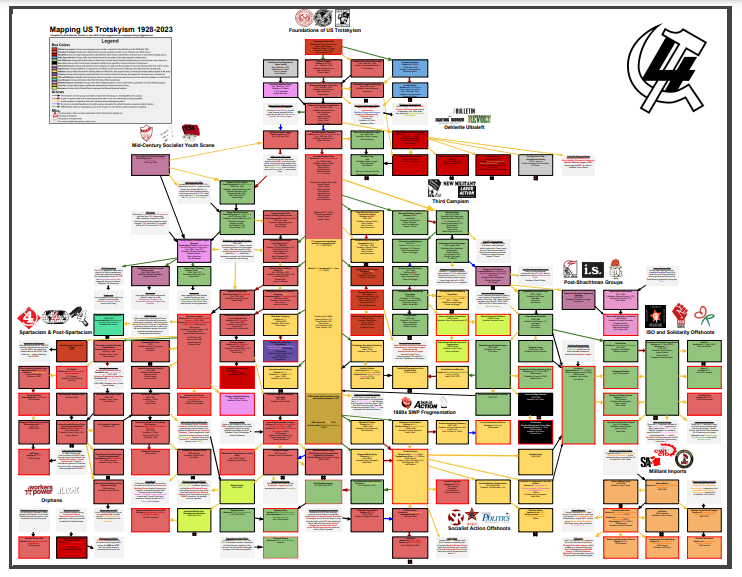

Of course, with two separate communist parties founded just 18 hours apart, it was clear that the division and factionalism were not over.

For a united party of action

The government stepped up its repression of both communist parties almost immediately. Many Communist leaders were driven underground or deported in the infamous “Palmer Raids.” Just over a year after the founding conventions, Ruthenberg was again targeted. He was convicted in November 1920 for “criminal syndicalism” for signing the Socialist Party Left Wing Manifesto and sent away to Sing Sing prison. The recommended sentence was 5 to 10 years, but after 18 months, he was out after an appeals court said he never should have been found guilty.

The two communist parties during this time united into a single Communist Party, thanks largely to negotiations led by Ruthenberg and Wagenknecht. John Reed had died in October 1920 in Russia, and Fraina was under a cloud of espionage and, eventually, embezzlement of party funds.

The unified party emerged from the underground as the Workers (Communist) Party, with Ruthenberg as its leader. But six weeks after he won his appeal and release, he and 16 others were arrested at a party convention in Bridgman, Michigan. The charge, again, was criminal syndicalism. Seeing that Ruthenberg was one of the ablest organizers and leaders in the Communist Party, security agencies and the police were determined to keep him isolated behind bars.

A new conviction was handed down, and Ruthenberg once more entered prison in January 1925, expecting to serve up to ten years. An appeal to the Supreme Court resulted in an order for a retrial, and 20 days later he was free once more pending further proceedings. The threat of re-imprisonment hung over his head from then until the day he died.

At a meeting of the party’s political committee in February 1927, Ruthenberg was jotting down notes when William Z. Foster told him that he looked pale. His only response was that he was “kind of under the weather.” A couple of hours later, he collapsed and was taken to emergency appendectomy surgery. He died three days later of acute peritonitis. Thousands packed a memorial meeting at Chicago’s Ashland Auditorium—the same hall where Ruthenberg had spoken at the launch of the Daily Worker in 1924. In honor of his wishes and at the request of the Communist International, his ashes were conveyed to Moscow, where he was interred just behind Lenin’s final resting place.

Through all the years of factionalism, sectarianism, and repression, Ruthenberg maintained his stance in favor of a united, legal, and practical party. Though some, like Fraina, would fade into obscurity or ignominy, Ruthenberg remained dedicated to building a party of socialism in the United States.

He was a devoted Marxist but had little sympathy for those who, on the basis of protecting their supposedly revolutionary principles, would have made the party into little more than a debating society. “The knowledge gained in study classes,” he wrote in his last Daily Worker column, “must be carried into the actual class struggle.”

His political legacy was captured in an article he wrote during the worst days of the intra-party factional fights. The Communist Party, he said in 1920, must be “a party of action,” must participate “in the everyday struggles of the workers and by such participation, inject its principles and give a wider meaning, thus developing the Communist movement.”

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes struggle sessions over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can go here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

shit. I think there was a same-titled movie as well?? if so, is it any good?

shit. I think there was a same-titled movie as well?? if so, is it any good?

,

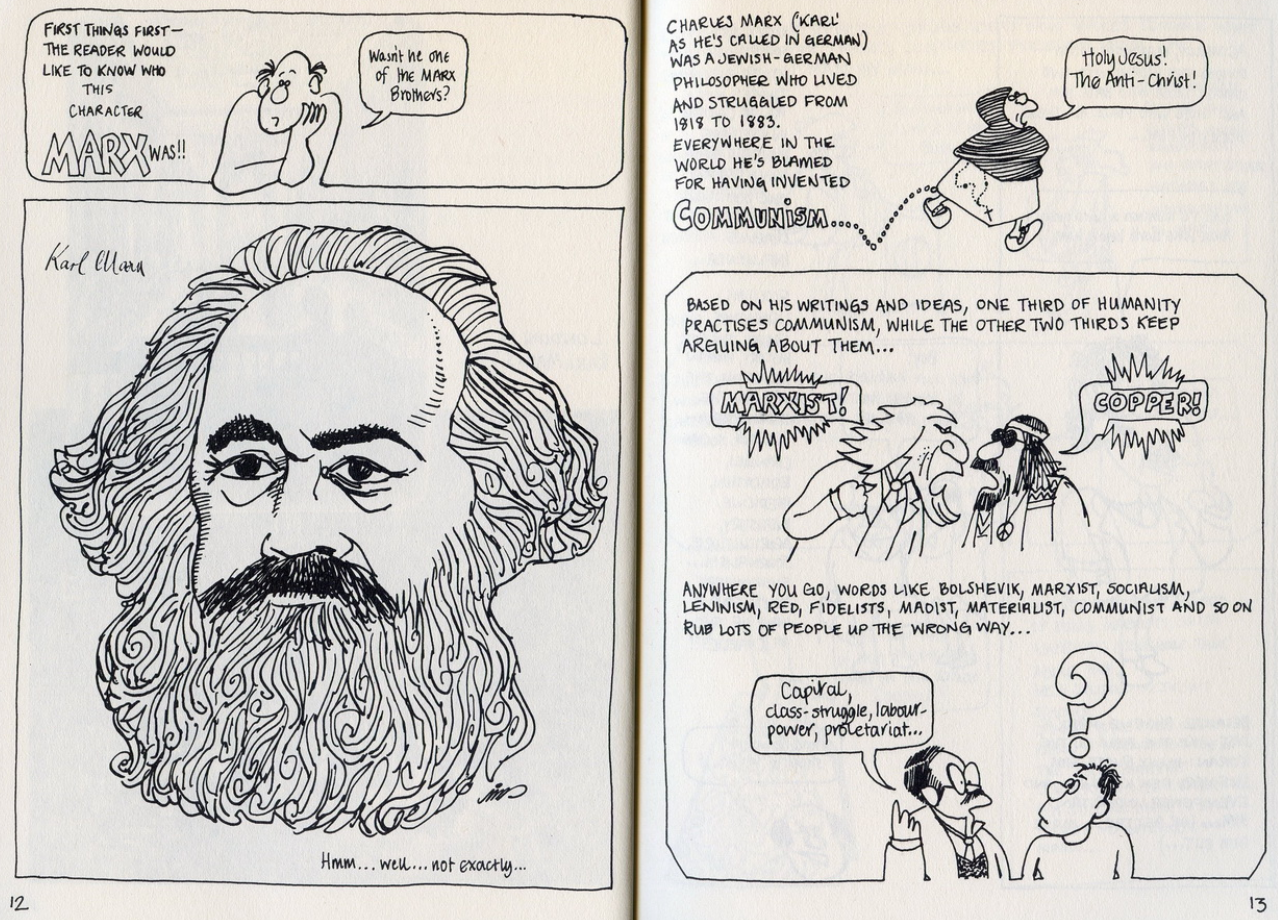

,  and learning more about a theorist I never knew about.

and learning more about a theorist I never knew about.