this post was submitted on 24 Oct 2023

115 points (100.0% liked)

games

20523 readers

140 users here now

Tabletop, DnD, board games, and minecraft. Also Animal Crossing.

-

3rd International Volunteer Brigade (Hexbear gaming discord)

Rules

- No racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, or transphobia. Don't care if it's ironic don't post comments or content like that here.

- Mark spoilers

- No bad mouthing sonic games here :no-copyright:

- No gamers allowed :soviet-huff:

- No squabbling or petty arguments here. Remember to disengage and respect others choice to do so when an argument gets too much

founded 4 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

brains

brains

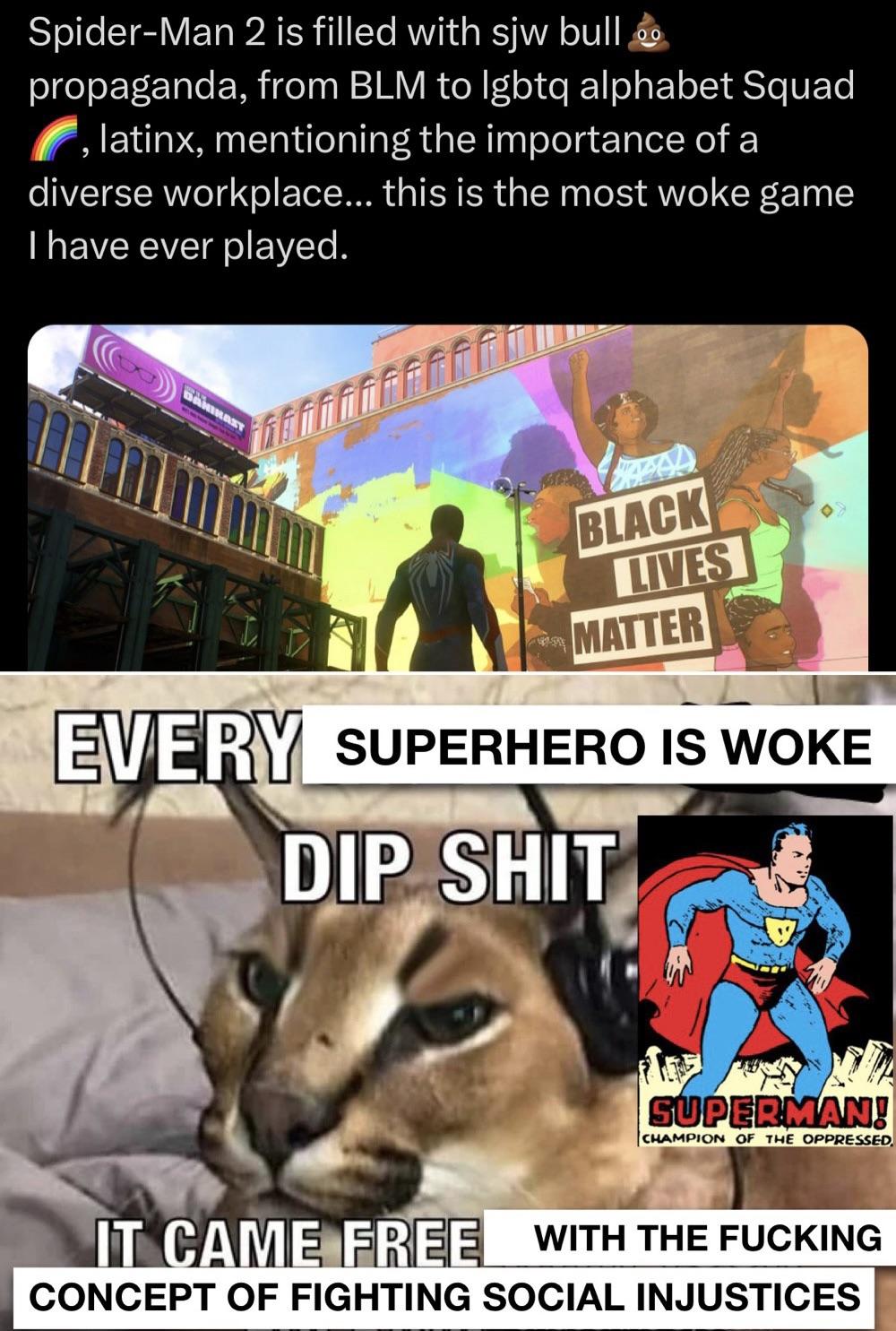

Ditko's objectivism is oversimplified and overstated. The reality is really telling. Kudos to an amazing piece of journalism by Jack Elving. So it seems Stan was the one who introduced a young Ditko to Rand. On top of that, Ditko really didn't put his politics into Spider-Man, most of that comes later AFTER he leaves Marvel for exploiting him.

cont

There is a lot more in the article, especially about Dr. Strange and I would highly recommend people check it out https://elvingsmusings.wordpress.com/2022/06/07/ditko-rand-the-objectivist-spider-man/

Hey thanks for the post! It's fun to make dumb jokes but I really appreciate you taking the time to share something interesting on the topic

Good read thanks for sharing