The other day I did a dive into a few sources at my disposal, in order to give an answer to this post. I'm reposting this into a new post since I think it was a fairly decent effort post that I'd like more people to read if interested:

I happened to stumble upon a pamphlet called "Lo que recibe el trabajador soviético además de su salario" (what the Soviet worker receives beside their salary), from 1959, written by A. Zveriev, the then minister of finance of the USSR. Please note that it uses contemporarily wrong-sounding words to refer to people with disabilities, such as "inválido" (which translates to something like non-valid, I've translated it to "disabled" in English for the text), which was the normal term back in the day in the Spanish-speaking world to refer to people with disabilities. Since then, the term first evolved to "minusválido" (less-valid), and contemporarily to "persona con discapacidad" (person with disability). In the section dedicated to social security, it briefly says:

"El problema de cómo asegurarse en la vejez, en caso de enfermedad y pérdida de la capacidad del trabajo, ha preocupado siempre y por doquier y sigue preocupando a millones de trabajadores. [...] El seguro social soviético abarca a todos los obreros y empleados [...]. Esta determinación de beneficiario no excluye del seguro ni a un solo obrero o empleado en caso de pérdida temporal de la capacidad del trabajo por enfermedad u otras causas. [...] Una peculiaridad del seguro social soviético es el alto nivel de asistencia que garantiza a los obreros y empleados y sus familias durante el período de enfermedad, embarazo y parto o pérdida de la capacidad de trabajo por otros motivos [...]

En caso de pérdida temporal de esta se pasan subsidios en la proporción del 50 al 90% del salario, según los años de servicio [...] Los subsidios por enfermedad o accidente se hacen efectivos desde el primer día de la baja hasta el total restablecimiento o declaración de inválido al paciente por una comisión de expertos médicos. En tal caso, éste pasa a la categoría de pensionado [...]

La suma total de subsidios por incapacidad temporal del trabajo en 1959 asciende a 11,000 millones de rublos, es decir, el quíntuple de la cantidad abonada en 1940. [...]

Las pensiones del Estado se adjudican por vejez e invalidez y en cáso de pérdida del cabeza de familia [...] Las pensiones por invalidez se estipulan según el grado de pérdida de la capacidad de trabajo, correspondiendo tarifas elevadas a los obreros y empleados que hubieran contraído la invalidez a causa de accidente de trabajo o enfermedad profesional. [...] para 1966 se prevé elevar [...] las [pensiones] de invalidez."

Translated to English:

"The problem of how to secure oneself in old age, in case of illness and loss of ability to work has always and everywhere concerned and continues to concern millions of workers. [...] Soviet social insurance covers all workers and employees [...]. This determination of beneficiary does not exclude a single worker or employee from insurance in case of temporary loss of ability to work due to illness or other causes. [...] A peculiarity of Soviet social insurance is the high level of assistance it guarantees to workers and employees and their families during the period of illness, pregnancy and childbirth or loss of ability to work for other reasons [...]

In case of temporary loss of ability to work, benefits are paid in the proportion of 50 to 90% of the salary, depending on the years of service [...] Benefits for illness or accidents are paid from the first day of sickness or accident until the patient is fully recovered or declared disabled by a commission of medical experts. In this case, they become a pensioner [...]

The total amount of benefits for temporary incapacity for work in 1959 amounts to 11 billion rubles, i.e. five times the amount paid in 1940. [...]

State pensions are awarded for old age and disability and in the event of the loss of the head of the family [...] Disability pensions are determined according to the degree of loss of working capacity, with higher rates for workers and employees who have become disabled as a result of an industrial accident or occupational disease. [...] for 1966 it is planned to raise [...] disability [pensions]."

So basically, it seems that people with disabilities that prevented them from working, were treated as pensioners, earning a pension proportional to how long they've worked and their salary during working years. Additionally, from the text:

"La administración de los seguros sociales está estructurada sobre amplios principios democráticos. La ejercen los sindicatos [...] lo cual garantiza el mejoramiento del servicio y el control de masas para que los fondos del Estado dirigidos a estos fines se utilicen convenientemente".

Or, in English:

"The administration of social security is structured on wide democratic principles. It's exerted by the unions [...], which guarantees the improvements of the service and control of masses so that the State funds allocated to these ends will be used conveniently".

From this, and the part before where it says that "a peculiarity is the high level of assistance it guarantees to workers and employees and their families", I deduce that by talking with the union representatives in case of a disabled family member as a worker, it would be possible to have access to some form of extra income, but I admit this is just my assumption.

Also relevant to the discussion, are some fragments from the book "Human rights in the Soviet Union", by Albert Szymanski (which I highly recommend to read). This book is 25 years younger than the former pamphlet, it was published in 1984 so the discussion is more nuanced in the sense that it includes data up to the early 80s. Not specific to people with disabilities, but definitely very important to them, is the following, from the introduction of Chapter 5 on Economic Rights:

"Housing and public transport in the USSR are also heavily subsidized; the standard fare on the Soviet subway is five kopecks (about eight cents) - a fare that has remained unchanged since the 1930s. Housing, medicine, transport and insurance account for an average of 15% of a Soviet family's income, compared to 50% in the US, while such services as higher education and child-care are either free or heavily subsidized"

Later in the chapter, in the section of "Social Consumption and the Social Wage":

"Over the years, the Soviets have been increasing the proportion of the total consumption of goods and services provided on the basis of need, i.e., the 'social wage', or the various social consumption goods and services, have increased in relation to the wage. For example, in 1940 the 'social wage' increased from 23% of the average take-home monthly cash wages, to 28% in 1950, 34% in 1960, 35% in 1970, and 38% in 1980 [...]. In 1980 the Sovits were spending an average of 438 roubles per capita on social consumption.[...] Because there has been virtually no infltion in the soviet economy over this period the great bulk of this increase corresponds to the real increase in socially consumed goods and services in the Soviet economy. In the 1970s the Soviets spent 23% of their net material product on social consumption, while social spending in the US was 17% of its GNP. [...] Consequently, in relative terms, the social wage adds considerably more to low than to high income families and, like Soviet pricing policy, thereby acts to increase real income inequality.[...]"

On the section about Healthcare:

"Drugs supplied in hospitals or prescribed for chronic illness (about 70% of all drugs) are provided free"

On the section about Job Rights:

The Soviet Constitution promises everyone a job [...]; there is no unemployment problem in the USSR [...]. Except in experimental enterprises, the legally permissible reasons for dismissing a worker are: [...] (7) long term disability[...]. With few exceptions, workers may be dismissed for any of the above stated reasons only with the concurrence of the local and factory trade union committees[...].

Republic-wide commissions exist for placing workers with enterprises that need labour. In addition to serving as labour exchanges, where workers and enterprises can systematically explore openings and available workers, they organize recruitment of wage labour, develop proposals for the employment of persons not currently employed (for example, housewives, older people) [I'm assuming that's also a possibility for people with disabilities who nonetheless can work] [...]. In the early 1970s about half of the new labour came through the use of these exchanges, the remainder was directly negotiated between individual workers and enterprises, through media advertising, posted openings and the word of mouth

Not only is a job considered to be a worker's right, but also working is considered to be a social duty. Soviet law stipulates that no one can live from rents, speculation, profits or black marketing [...]. Living off savings or being supported by parents, friends or spouses is, however, not illegal. There is no law requiring everyone to work, but social pressure is applied against people who live for lengthy periods without themselves working"

So, while there's not much in the way of specific discussion regarding people with disabilities, I'll make some commentary.

Of course, the USSR for most of its history was relatively a "developing nation", with the highest levels of material wealth, and therefore material well-being, being achieved mostly during and after the 70s and until the Perestroika. Despite this, the SOCIAL RIGHT to a job for everyone who is capable of working, without any discrimination, and the absolute lack of unemployment (Szymanski: "About 60% of dismissed workers were able to find new employment within ten days of their dismissal"), likely resulted in a majority of people with disabilities that don't prevent them from working being able to find jobs. Since unions that were involved in the process of firing someone from a job, it seems to me highly unlikely that a person with disabilities would be fired from a job just for the sake of it, and the chronic labour shortage of the USSR (by design, in order to maximize the output of the economy and guaranteeing everyone a job), as well as the well-functioning State mechanisms to find people jobs, makes me believe that most people with disabilities were perfectly capable of finding and maintaining a job.

In the case of people with disabilities that rendered them unable to work, it's rather clear to me from the previous pamphlet that they were treated as pensioners. The pamphlet specifically says "disability pensions are determined according to the degree of loss of working capacity". It's likely that these pensions were generally low, especially so during the earlier years of development of the USSR's economy, but it's necessary to keep in mind that the costs of the basics were very heavily subsidized, as the book says, "Housing, medicine, transport and insurance account for an average of 15% of a Soviet family's income". So, while it's likely that many people with disabilities likely relied partially on family members as a supplementary form of income, which isn't ideal, it's absolutely not worse than the case of modern liberal societies, where that absolutely happens (in my experience as a Spanish guy who fortunately enjoys EU levels of social security, I can't imagine how bad it is in the USA).

Furthermore, the RIGHT TO A JOB makes me believe wholeheartedly that it was much more likely for people with disabilities to find a job suited to their capabilities. After all, the form of socialism in the USSR, was "from each according to their work; to each according to their needs". I find this perspective much more humanizing than the systematically high unemployment rates for people with disabilities in capitalist societies, in which even in countries with stronger social security, companies in many cases hire people with disabilities for tax exemptions, or where people who by all means can work many jobs despite some disabilities, are exluded from the job market and relegated to feeling like a social burden by living off a pension.

I understand that this analysis was very economics-focused, and it lacks a lot in the societal sense, architectural design, etc. It would be very interesting to focus on how the public transit-oriented transportation system creates higher mobility for most people with movement impairments, the architectural design (which I have absolutely no idea about), or many other aspects of life for people with disabilities, but unfortunately I can't provide anything else for the time being. Anyway, thanks a bunch for reading, it was a pleasure to write this down.

Also, lots of civilians die in wars like the one happening in Gaza, it's sad but inevitable"

Also, lots of civilians die in wars like the one happening in Gaza, it's sad but inevitable"

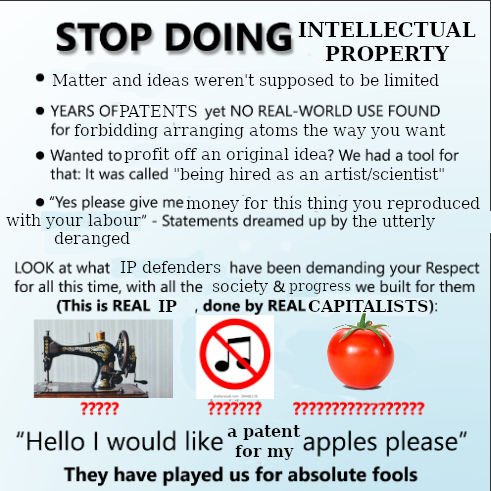

Yeah, it makes no sense to allow the patenting of literal living creatures...

Another funny one to me is tools and machines, it's literally telling people: "NO! ONLY I CAN ARRANGE ATOMS IN THIS ORDER!!!!!" Kinda wild that we allow that