An interesting and short article by Gramsci on bourgeois conceptions of history, and important dates.

This text was first published in Avanti!, Turin edition, from his column “Sotto la Mole,” January 1, 1916.

Every morning, when I wake again under the pall of the sky, I feel that for me it is New Year’s day.

That’s why I hate these New Year’s that fall like fixed maturities, which turn life and human spirit into a commercial concern with its neat final balance, its outstanding amounts, its budget for the new management. They make us lose the continuity of life and spirit. You end up seriously thinking that between one year and the next there is a break, that a new history is beginning; you make resolutions, and you regret your irresolution, and so on, and so forth. This is generally what’s wrong with dates.

They say that chronology is the backbone of history. Fine. But we also need to accept that there are four or five fundamental dates that every good person keeps lodged in their brain, which have played bad tricks on history. They too are New Years’. The New Year’s of Roman history, or of the Middle Ages, or of the modern age.

And they have become so invasive and fossilising that we sometimes catch ourselves thinking that life in Italy began in 752, and that 1490 or 1492 are like mountains that humanity vaulted over, suddenly finding itself in a new world, coming into a new life. So the date becomes an obstacle, a parapet that stops us from seeing that history continues to unfold along the same fundamental unchanging line, without abrupt stops, like when at the cinema the film rips and there is an interval of dazzling light.

That’s why I hate New Year’s. I want every morning to be a new year’s for me. Every day I want to reckon with myself, and every day I want to renew myself. No day set aside for rest. I choose my pauses myself, when I feel drunk with the intensity of life and I want to plunge into animality to draw from it new vigour.

No spiritual time-serving. I would like every hour of my life to be new, though connected to the ones that have passed. No day of celebration with its mandatory collective rhythms, to share with all the strangers I don’t care about. Because our grandfathers’ grandfathers, and so on, celebrated, we too should feel the urge to celebrate. That is nauseating.

I await socialism for this reason too. Because it will hurl into the trash all of these dates which have no resonance in our spirit and, if it creates others, they will at least be our own, and not the ones we have to accept without reservations from our silly ancestors.

– Translated by Alberto Toscano

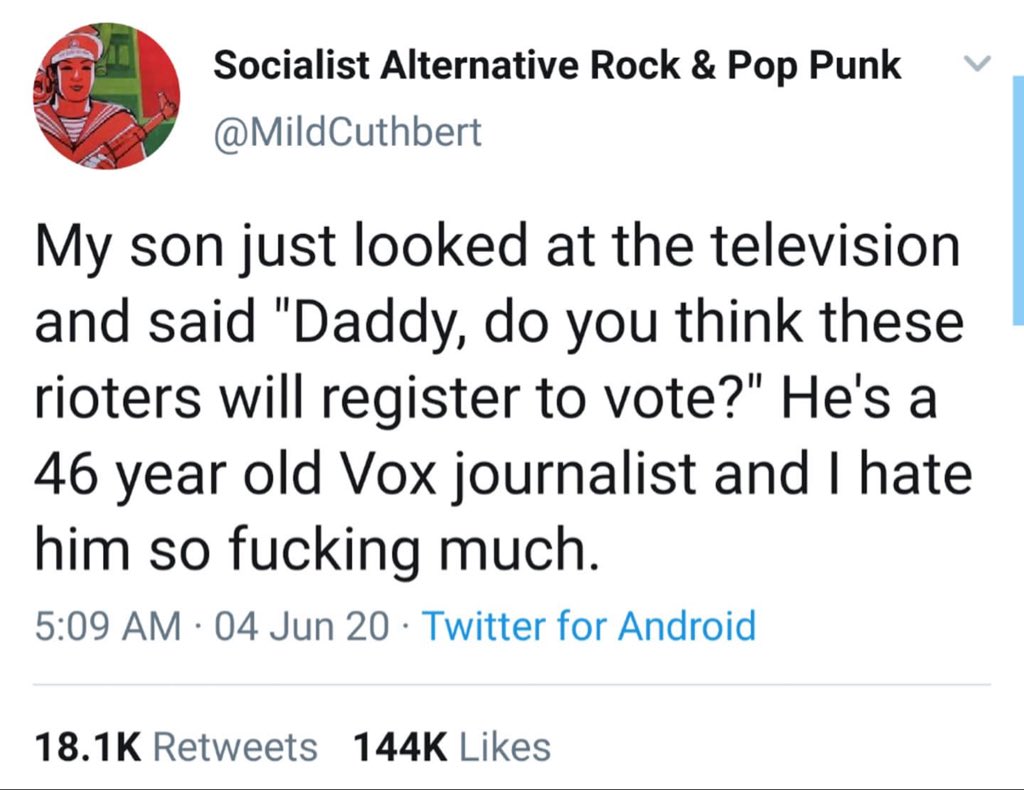

I think this reply perfectly justifies Roderic's position on seriousness. You just strawman his argument to mean "100% seriousness all the time, no fun allowed at all" and then proceed to write some nonsense against it.

Do you really think the western left is serious enough? What has it accomplished? Do you think others will take us seriously if we don't take ourselves seriously, and how can we accomplish anything at all, let alone revolution, if we're not serious about it?