Link to parent tweet

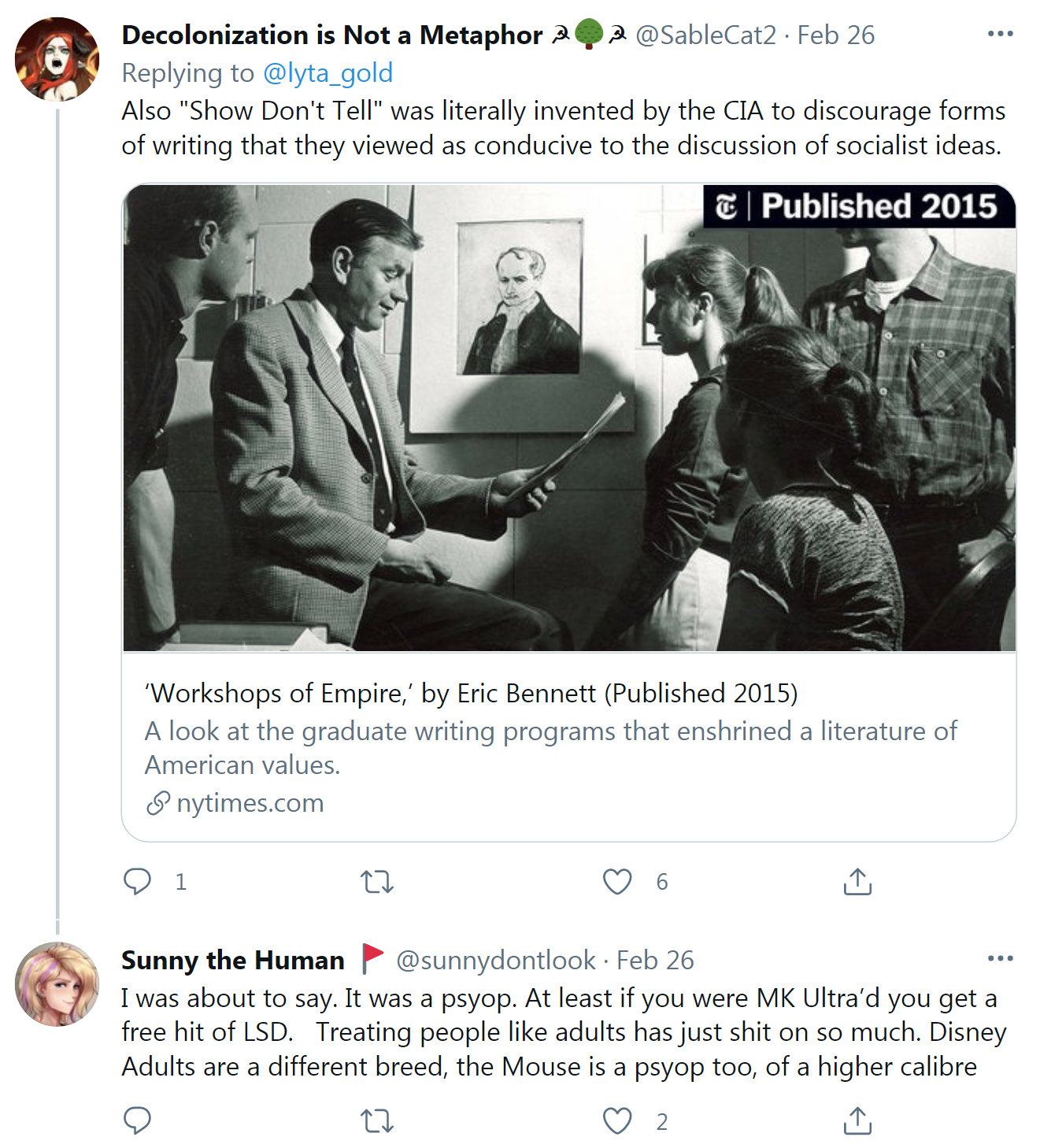

Text of the NYT Article:

By Timothy Aubry

Nov. 25, 2015

Less than a lifetime ago, reputable American writers would occasionally start fistfights, sleep in ditches and even espouse Communist doctrines. Such were the prerogatives and exigencies of the artist’s existence, until M.F.A. programs arrived to impose discipline and provide livelihoods. Whether the professionalization of creative writing has been good for American literature has set off a lot of elegantly worded soul-searching and well-mannered debate recently, much of it in response to Mark McGurl’s seminal study, “The Program Era.” What Eric Bennett’s “Workshops of Empire” contributes is an understanding of how Cold War politics helped to create the aesthetic standards that continue to rule over writing workshops today.

Sponsored by foundations dedicated to defeating Communism, creative-writing programs during the postwar period taught aspiring authors certain rules of propriety. Good literature, students learned, contains “sensations, not doctrines; experiences, not dogmas; memories, not philosophies.” The goal, according to Bennett, was to discourage the abstract theorizing and systematic social critiques to which the radical literature of the 1930s had been prone, in favor of a focus on the personal, the concrete and the individual. While workshop administrators like Paul Engle and Wallace Stegner wanted to spread American values, they did not want to be caught imposing a particular ideology on their students, for fear of appearing to use the same tactics as the communists. Thus they presented their aesthetic principles as a nonpolitical, universally valid means of cultivating writerly craft. The continued status of “show, don’t tell” as a self-evident truth, dutifully dispensed to anyone who ventures into a creative-writing class, is one proof of their success.

Bennett’s argument is a persuasive reminder that certain seemingly timeless criteria of good writing are actually the product of historically bound political agendas, and it will be especially useful to anyone seeking to expand the repertoire of stylistic strategies taught within creative-writing programs. That said, some sections are better researched than others. His chapters on Stegner, Hemingway and Henry James lack the detailed institutional machinations that make his account of Engle’s career so compelling. Moreover, he uses the early history to support his claim that creative-writing programs continue to bolster a pro-capitalist worldview today. But a chess move made to solve specific problems can serve unexpected purposes when the situation on the board has changed. Whether or not the aesthetic doctrines currently championed by writing workshops perform the same political function they once did, now that the very conflict responsible for their emergence has ended, is a question that requires further study.

Finally, despite Bennett’s misgivings about creative-writing workshops, his book is itself a convincing argument in their favor. A graduate of the Iowa M.F.A. program, Bennett has produced a literary history far more enjoyable than the typical academic monograph, for all the reasons one might guess. It features a winning protagonist, Engle, the ebullient poet-huckster and early director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, who, according to Bennett, “moved too quickly through the airports and boardroom offices to bother with the baggage of complex beliefs.” Here and elsewhere, Bennett never tells when he can show. The 1920s, under his scrutiny, consists not of trends, but of “racy advertisements, voting mothers, unruly daughters, smoking debutants, migrating Negroes, Marx, Marxists, Freud, Freudians and the unsettling monstrosity of canvasses and symphonies from Europe.” Wallace Stegner, he observes, “wrote at length about not sleeping with people.” Whether novelists and poets should make room in their work for the intellectual abstractions that prevail within academic scholarship, the academy would be better off if more of its members could attend to concrete particulars with the precision and wit that Bennett brings to his subject. Indeed, they might even benefit from taking a creative-writing class or two.

WORKSHOPS OF EMPIRE

Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing During the Cold War

Link to the article

I feel like, roughly coinciding with Mamdani's win last week, my For You page on Twitter is just crawling with reactionary slop. I mean, Twitter always has been, and there was a noticeable uptick when Elon first took over of overtly fash accounts, who neither I nor anyone I follow seemed to interact with in any way, showing up in my feed. But the last week or so I've gotten just a ton of like goofy racist stuff. Maybe I interacted with a few bad posts and the Twitter algo has decided I should be served this content. Or it's possible that when Tucker Carlson was running rings around Ted Cruz that a few of the accounts I liked making fun of Cruz were these right-wingers. Whatever.

In the last half hour I've seen a video where the post said "beware where you get your takeout" and you could see the video was in a kitchen. I figured it was going to be some slighly slop-like content where inspectors go into a kitchen and find roaches or something so I click the video. And it's some British guy who barges into a kitchen and is mad that migrants work there. There was another one of a guy walking through some sort of market in Rome, and he was the only white around, and he was bemoaning the fall of the West. I saw a post from a veteran claiming that Muslims are evil savages, and we can't let Mamdani take New York.

I spend a lot of time doomscrolling Twitter and the sudden proliferation of this stuff (and I'm getting a lot of slop and video content that isn't relevant to me in my feed generally, not just this shit) might be what finally gets me to quit Twitter.